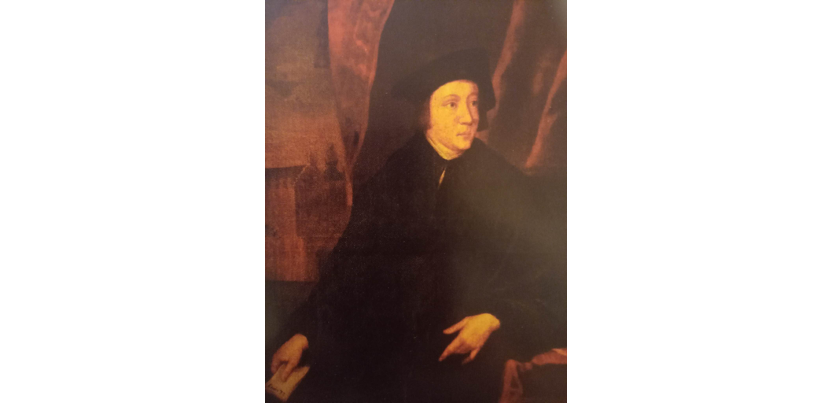

ABOVE: Portrait of Eustace Chapuys by an unknown artist, 17th century

With the rarest of exceptions, everyone, academics and enthusiasts alike, can look back at the accusations and proceedings against Anne Boleyn and the five men she was accused with and say without doubt that they were innocent. In fact, as Eric Ives states in his definitive biography ‘The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn,’ we can prove that Anne and her alleged lovers were not in the same place on the dates they were accused of liasing on. It is clear to us, particularly with our modern sense of justice and rule of law, that it was a complete, trumped-up sham.

But these feelings are not new. In fact, even Anne’s most serious detractors had serious doubts about the proceedings. No less a man than Eustace Chapuys, Spanish Ambassador, partisan of Katherine of Aragon and Mary, sworn enemy of Anne, the woman he referred to as ‘putain,’ was quite dismissive of the case against her, stating she and the men were ‘condemned upon presumption and certain indications, without valid proof or confession.’ He wrote to his master, Emperor Charles V, that whilst people were ‘rejoicing’ at Anne’s downfall, there were ‘ill’ feelings about the proceedings.

Though Chapuys’ letters must be taken with a grain of salt when it comes to the factual recounting of events, that is usually because he was promoting an anti-Anne agenda; he was generally willing to believe anything that cast Anne in a bad light. That even he was doubtful of her guilt speaks volumes.

Between Anne’s arrest and execution, Chapuys wrote two letters to Charles V; there is a suggestion that he was unable to write more because he had been ill with tertian fever. Below are the two letters. He refers to Jane Seymour as ‘Mrs. Semel,’ but from descriptions in these letters and others, it is very clear this is who he is referring to. I have truncated the second letter somewhat where Chapuys begins discussing unrelated matters out of context for ease of reading.

~

2ND MAY, 1533

‘Your Majesty will remember what I wrote about the beginning of last month, of the conversation I had with Cromwell about the divorce of this King from the Concubine. I have since heard the will of the Princess, by which, as I wrote, I meant to be guided, and which was that I should promote the matter, especially for the discharge of the conscience of the King her father, and that she did not care in the least if he had lawful heirs who would deprive her of the succession, nor for all the injuries done either to herself or to the Queen her mother, which, for the honor of God, she pardoned everyone most heartily. I accordingly used several means to promote the matter, both with Cromwell and with others, of which I have not hitherto written, awaiting some certain issue of the affair, which, in my opinion, has come to pass much better than anybody could have believed, to the great disgrace [of the Concubine], who by the judgment of God has been brought in full daylight from Greenwich to the Tower of London, conducted by the duke of Norfolk, the two Chamberlains, of the realm and of the chamber, and only four women have been left to her. The report is that it is for adultery, in which she has long continued, with a player on the spinnet of her chamber, who has been this morning lodged in the Tower, and Mr. Norris, the most private and familiar “somelier de corps” of the King, for not having revealed the matter.

The Concubine’s brother, named Rochefort, has also been lodged in the Tower, but more than six hours after the others, and three or four before his sister; and even if the said crime of adultery had not been discovered, this King, as I have been for some days informed by good authority, had determined to abandon her; for there were witnesses testifying that a marriage passed nine years before had been made and fully consummated between her and the earl of Northumberland, and the King would have declared himself earlier, but that some one of his Council gave him to understand that he could not separate from the Concubine without tacitly confirming, not only the first marriage, but also, what he most fears, the authority of the Pope. These news are indeed new, but it is still more wonderful to think of the sudden’ change from yesterday to today, and the manner of the departure from Greenwich to come hither; but I forbear particulars, not to delay the bearer, by whom you will be amply informed.

As to the matters of France, I think they are in no great favor here. The French ambassador had a courier on Saturday; nevertheless, either for pride or disdain, he let himself be sent for twice before he would go to Court, from which he returned not over well pleased. The English had despatched a courier to France eight days ago, but they sent in great haste to recall him, and I have not heard that they have sent any one since. London, 2 May, Eve of the Invention of Holy Cross, 1536.’

~

19 MAY, 1533

‘…On the 11th were condemned as traitors Master Noris, the King’s chief butler, (sommelier de corps) Master Ubaston (Weston), who used to lie with the King, Master Bruton (Brereton), gentleman of the Chamber, and the groom (varlet de chambre), of whom I wrote to your Majesty by my man. Only the groom confessed that he had been three times with the said putain and Concubine. The others were condemned upon presumption and certain indications, without valid proof or confession. On the 15th the said Concubine and her brother were condemned of treason by all the principal lords of England, and the duke of Norfolk pronounced sentence. I am told the earl of Wiltshire (Voulcher) was quite as ready to assist at the judgment as he had done at the condemnation of the other four. Neither the putain nor her brother was brought to Westminster like the other criminals. They were condemned within the Tower, but the thing was not done secretly, for there were more than 2,000 persons present. What she was principally charged with was having cohabited with her brother and other accomplices; that there was a promise between her and Norris to marry after the King’s death, which it thus appeared they hoped for; and that she had received and given to Norris certain medals, which might be interpreted to mean that she had poisoned the late Queen and intrigued to do the same to the Princess. These things she totally denied, and gave to each a plausible answer. Yet she confessed she had given money to Voaiston (Weston), as she had often done to other young gentlemen. She was also charged, and her brother likewise, with having laughed at the King and his dress, and that she showed in various ways she did not love the King but was tired of him. Her brother was charged with having cohabited with her by presumption, because he had been once found a long time with her, and with certain other little follies. To all he replied so well that several of those present wagered 10 to 1 that he would be acquitted, especially as no witnesses were produced against either him or her, as it is usual to do, particularly when the accused denies the charge.

I must not omit, that among other things charged against him as a crime was, that his sister had told his wife that the King “nestoit habile en cas de soy copuler avec femme, et quil navoit ne vertu ne puissance.” This he was not openly charged with, but it was shown him in writing, with a warning not to repeat it. But he immediately declared the matter, in great contempt of Cromwell and some others, saying he would not in this point arouse any suspicion which might prejudice the King’s issue. He was also charged with having spread reports which called in question whether his sister’s daughter was the King’s child. To which he made no reply. They were judged separately, and did not see each other. The Concubine was condemned first, and having heard the sentence, which was to be burnt or beheaded at the King’s pleasure, she preserved her composure, saying that she held herself “pour toute saluee de la mort,” and that what she regretted most was that the above persons, who were innocent and loyal to the King, were to die for her. She only asked a short space for shrift (pour disposer sa conscience). Her brother, after his condemnation, said that since he must die, he would no longer maintain his innocence, but confessed that he had deserved death. He only begged the King that his debts, which he recounted, might be paid out of his goods.

Although everybody rejoices at the execution of the putain, there are some who murmur at the mode of procedure against her and the others, and people speak variously of the King; and it will not pacify the world when it is known what has passed and is passing between him and Mrs. Jane Semel. Already it sounds ill in the ears of the people, that the King, having received such ignominy, has shown himself more glad than ever since the arrest of the putain; for he has been going about banqueting with ladies, sometimes remaining after midnight, and returning by the river. Most part of the time he was accompanied by various musical instruments, and, on the other hand, by the singers of his chamber, which many interpret as showing his delight at getting rid of a “maigre vieille et mechante bague,” with hope of change, which is a thing specially agreeable to this King. He supped lately with several ladies in the house of the bishop of Carlisle, and showed an extravagant joy, as the said Bishop came to tell me next morning, who reported, moreover, that the King had said to him, among other things, that he had long expected the issue of these affairs, and that thereupon he had before composed a tragedy, which he carried with him; and, so saying, the King drew from his bosom a little book written in his own hand, but the Bishop did not read the contents. It may have been certain ballads that the King has composed, at which the putain and her brother laughed as foolish things, which was objected to them as a great crime.

…

Today Rochford has been beheaded before the Tower, and the four others above named, notwithstanding the intercession of the bishop of Tarbes, the French ambassador resident, and the sieur de Tinteville, who arrived the day before yesterday, in behalf of one named Vaston (Weston). The Concubine saw them executed from the Tower, to aggravate her grief. Rochford disclaimed all that he was charged with, confessing, however, that he had deserved death for having been so much contaminated and having contaminated others with these new sects, and he prayed everyone to abandon such heresies. The Concubine will certainly be beheaded tomorrow, or on Friday at the latest, and I think the King feels the time long that it is not done already. The day before the putain’s condemnation he sent for Mrs. Semel by the Grand Esquire and some others, and made her come within a mile of his lodging, where she is splendidly served by the King’s cook and other officers. She is most richly dressed. One of her relations, who dined with her on the day of the said condemnation, told me that the King sent that morning to tell her that he would send her news at 3 o’clock of the condemnation of the putain, which he did by Mr. Briant, whom he sent in all haste. To judge by appearances, there is no doubt that he will take the said Semel to wife; and some think the agreements and promises are already made.

…

Having written the above the day before yesterday, thought it well to delay the despatch to inform the Emperor of the execution of the Concubine, which was done at 9 o’clock this morning within the Tower, in presence of the Chancellor, Cromwell, and others of the Council, and a great number of the King’s subjects, but foreigners were not admitted. It is said that although the bodies and heads of those executed the day before yesterday have been buried, her head will be put upon the bridge, at least for some time. She confessed herself yesterday, and communicated, expecting to be executed, and no person ever showed greater willingness to die. She requested it of those who were to have charge of it, and when the command came to put off the execution till today she appeared very sorry, praying the Captain of the Tower that for the honor of God he would beg the King that, since she was in good state and disposed for death, she might be dispatched immediately. The lady who had charge of her has sent to tell me in great secresy that the Concubine, before and after receiving the sacrament, affirmed to her, on the damnation of her soul, that she had never been unfaithful to the King. London, 19 May 1536.’

[…] I touched upon in my post about Chapuys’ perspective on Anne’s guilt, which you can read here. Nor were people necessarily glad to see Jane Seymour take her place, regardless of how much she […]