Henry VII and Elizabeth of York are well-known as the parents of Arthur, Margaret, Henry, and Mary. The lives of the latter three are particularly renowned for the extreme highs and lows of fortune they faced. In this family portrait, however, you will notice that there are actually 7 children depicted. Like most couples during this period, Henry and Elizabeth lost children far too early – Elizabeth, Edmund, and Catherine.

Elizabeth was born on the 2nd July, 1492, at Sheen Palace, and was presumably named after her mother. Her short life was predominantly spent in the royal nursery at Eltham Palace, where she was cared for by wet nurses Cecily Burbage and Alice Davy, and by cradle rockers Margaret Traughton, Anne Mayland, and Margery Gower. Sadly, Elizabeth died when she was just 3 years old on the 14th September, 1495. She was buried in the chapel of St. Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey, in a tomb made from Purbeck and black marble. A Latin inscription, now too faded to read, was translated as:

‘Elizabeth, second child of Henry the Seventh King of England, France and Ireland and of the most serene lady Queen Elizabeth his consort, who was born on the second day of the month of July in the year of Our Lord 1492, and died on the 14th day of the month of September in the year of Our Lord 1495, upon whose soul may God have mercy. Amen.’

The plate at the feet of her effigy is translated:

‘Hereafter Death has a royal offspring in this tomb viz. the young and noble Elizabeth daughter of that illustrious prince, Henry the Seventh, who swayed the sceptre of two kingdoms, Atropos, the most severe messenger of Death, snatched her away but may she have eternal life in Heaven.’

Thomas More wrote in his ‘Elegy on Elizabeth of York,’ a poignant tribute to the young Elizabeth:

‘Adieu sweetheart! My little daughter late, thou shalt, sweet babe, such is thy destiny, thy mother never know; for here I lie… At Westminster, that costly work of yours, mine own dear lord, I shall never see.’

Four and a half years after young Elizabeth’s death, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York welcomed a son, named Edmund, on the 21st February, 1499. He was named for his paternal grandfather, and had Lady Margaret Beaufort, Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Richard Foxe as his godparents. Edmund was also raised in the nursery at Eltham Palace, and was there with Margaret, Henry, and Mary, when they were visited by Erasmus and Thomas More in September, 1499. Though not formally invested with the title, young Edmund was referred to as the duke of Somerset. His parents were travelling from Calais when they received the news of Edmund’s death on the 19th June, 1500, possibly from the plague; the royal children had moved from Eltham Palace to Hatfield House to try and avoid the disease which was rampant that summer. Edmund held a state funeral, and was buried near his sister Elizabeth in Westminster Abbey, for which Henry VII paid £242. It is unclear if any monument was commissioned for Edmund, but if there was one, it no longer exists.

Finally, on the 2nd February, 1503, Elizabeth of York gave birth to Catherine, possibly named for her father’s forbearer, Catherine of Valois. Less than a year earlier, the child’s eldest brother, Arthur, had died of a much-speculated-upon illness, to the devastation of the entire family. More tragedy was to follow, as within a few days, Catherine passed away. On the 11th February, her 37th birthday, Elizabeth of York also died due to a postpartum infection. Though we know Catherine was buried in Westminster Abbey, no monument survives, and the location of her tomb is unknown. Personally I would like to believe she was buried with her mother, though there is nothing to indicate that this was the case.

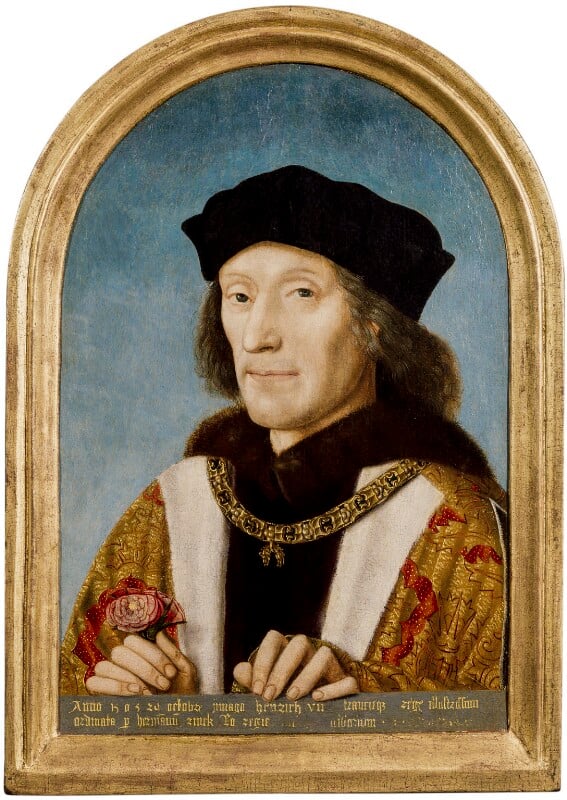

The fact that Edmund and Catherine have no monuments to memorialise them would seem to suggest that they were not deeply mourned, just seen as more victims to the high infant mortality rates of this period. However, the painting at the top of this article, commissioned by Henry VII at some point between Catherine’s birth and death in 1503, and Henry’s own death in 1509, shows that Henry did remember his lost children. It seems this piece was originally an altarpiece for the royal chapel at Richmond Palace; a piece for personal contemplation rather than ostentatious display. And in any case, their early deaths meant that Elizabeth, Edmund, and Catherine had no dynastic significance. They were included because they were loved, remembered, and grieved.

Image at top: The Family of Henry VII with St George and the Dragon, by an unknown artist, c.1505-1509.

Henry VII and Elizabeth of York are the two central most figures each side of the angel, with their children behind them, including, touchingly, Elizabeth, Edmund and Catherine, who had died in infancy

UPDATE:

I wanted to provide an update regarding the inscription on young Elizabeth’s tomb. As Linda Porter – historian rightly pointed out, the translation of the Latin text gives Elizabeth as the second child, instead of the fourth. The translation was based on information from Westminster Abbey, so I got in touch with Dr. Matthew Payne, Keeper of the Muniments at Westminster Abbey, to try and find out whether this was an issue with the original Latin inscription or a later translation.

It seems renowned antiquarian, William Camden, recorded the transcription in his ‘Reges, Reginae, Nobiles et Alii in Ecclesia Collegiata B Petri Westomonatserii’ (1600). Camden had access to the original brass plate with the inscription, and recorded it thus:

‘Elizabetha Illustrissimi Regis Angliae, Franciae & Hiberniae Henrici Septimi, & Domine Elizabethe serenissime consortis sue filia & secunda proles, que nata fuit secundae die mensis Julii anno domini 1492 & obiit decimo quarto die mensis Septembris anno dom. 1495. cuius anime propitietur Deus. Amen.’

The section of the text that concerns us is ‘sue filia & secunda proles,’ which translates to ‘his daughter and second child.’ Now, an 18th century historian, John Dart, who seemingly took his transcription from Camden (he notes the inscription was no longer present) translated ‘secunda proles’ as second daughter, however either he was mistaken in his translating or was correcting it to what he knew to be factual. ‘Proles’ means child or offspring and is not gendered. Similarly, ‘secunda’ is a feminine adjective, and does not suggest the gender of the noun.

There are several explanations for what is happening here, some of which could be Camden’s transcription was incorrect, the author of the inscription wrote the text incorrectly, or the artisan who inscribed the text on the brass plate made an error. But it seems like a very simple thing for Camden to get wrong, and given that those involved in creating a monument for the king’s daughter would be highly skilled, those explanations just don’t convince me. Personally, I think the most likely explanation is poetic license.

The translation provided by Westminster Abbey, which I quote in my original post was rendered as: ‘Elizabeth, second child of Henry the Seventh King of England…’ However, when looking at how the original Latin puts it ‘sue filia & secunda proles,’ a more literal translation (based on my admittedly far-from-perfect Latin) would be ‘Elizabeth, of the most Illustrious King of England, France and Ireland, Henry the Seventh, and the most serene Queen Elizabeth his consort, daughter and second child…’ It is understandable that a composer did not wish to write it ‘sue filia & secunda filia’ – repeating the same noun twice in a sentence is lexically uncomfortable.

We can debate why they didn’t just change how it was written in the first place; for example, just putting it as ‘secunda filia,’ ‘sue secunda filia,’ or ‘secunda filia eius’ in the first place, all of which could be translated as ‘his second daughter,’ without bringing in ‘proles’ a second phrase. I’m sure someone with a better grasp of medieval Latin can provide a more elegant turn of phrase than my rough renditions.

But all of that is speculative. The fact is, this is how it was written. To our eyes, it comes across as inaccurately placing Elizabeth as the second child when she was the fourth, but I think it is most likely that a more poetic interpretation is supposed to correctly place her as the second daughter.

Many thanks to Linda Porter – historian for prompting me to look further into this, and to Keeper of the Muniments, Dr. Matthew Payne for providing me with the details of the provenance of the transcription and translation.