Following the Norman Conquest, the kings of England were identified in contemporary documents not by the regnal numbers we know them by today, but by patronymic identifiers. For example, Henry III was instead named in written documents as King Henry, son of King John. This system worked well, until we came to Henry’s son and his successors. Edward II did not pose too much of an issue, ‘King Edward, son of King Edward’ was not too bad; but when he was followed by another King Edward, it got a bit trickier.

They couldn’t call Edward III ‘King Edward, son of King Edward’, that was his father. Documents from the first few months of his reign struggled with this. The Calendar of Close Rolls preserves an entry on the 5th March, 1327, just over a month after Edward’s ascension, which refers to him as ‘King Edward, son of King Edward, son of King Edward, son of Henry,’ in order to make it clear who the king was. But very quickly a new form emerged: ‘King Edward, the third after the Conqueror.’

Such enumeration was not completely new, but it wasn’t common. In fact, one of the earliest cases of regnal numbering raises questions about the form used for Edward III. His grandfather, Edward I as we know him, was numbered in at least two texts written shortly after his death in 1307. The first, a testimony given in the case for the canonisation of Thomas de Cantilupe on the 29th August, 1307, actually enumerates Edward’s father as well:

‘…seneschallus regis henrici tercii patris inclite memorie domini Edwardi quarti regis Anglorum…’

(…seneschal of king henry the third’s father to the illustrious memory of lord Edward the fourth, king of england…)

A eulogy written for Edward in the same year names him similarly:

‘transitu magni regis Edwardi quarti’

(the passing of the great king Edward the fourth)

The fact that he was named in this form was an acknowledgement of the fact that we had a King Edward succeeding a King Edward, and therefore a need to distinguish them from one another. The need just didn’t become so great until they reached a third in a row.

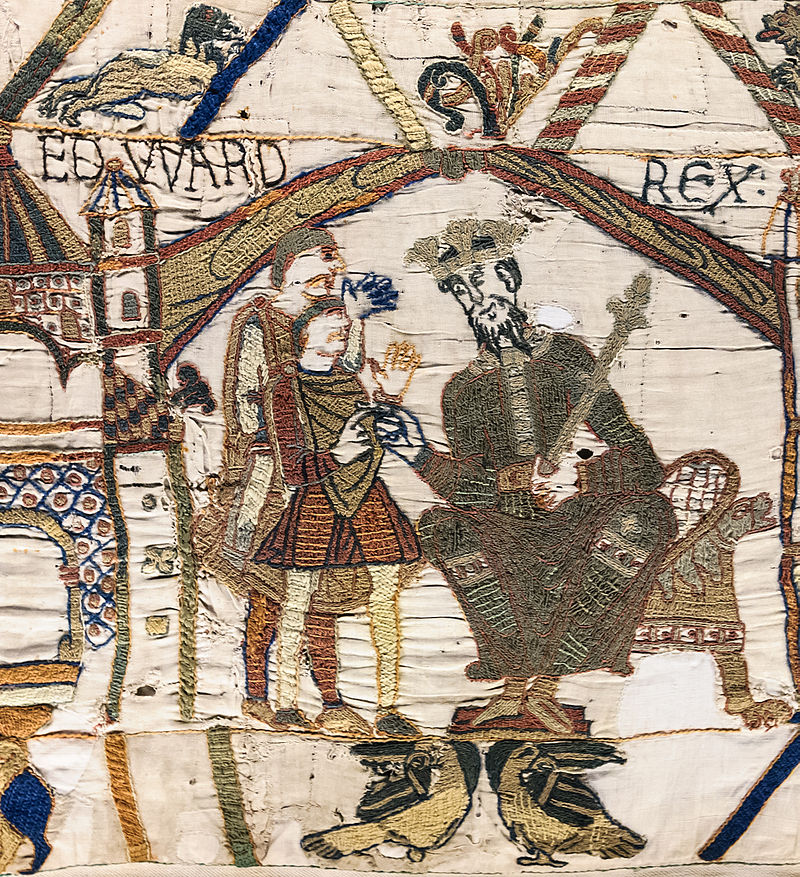

What will stand out, of course, is that the king we know as Edward I was labelled as the fourth. This takes into account the Anglo-Saxon King Edwards: Edward the Elder (874-924), Edward the Martyr (962-978), and Edward the Confessor (1003-1066). The Anglo-Saxon kings were distinguished by descriptive phrases, which was continued through the High Middle Ages, such as Henry of Winchester (Henry III), Edward Longshanks (Edward I) and Edward of Caenarfon (Edward II). By the 14th century, however, these types of names were not frequently used in official documents, probably because they were considered too informal. By labelling Edward I as ‘the fourth,’ it positioned Edward the Elder, the Martyr, and the Confessor as first, second, and third respectively. This actually does continue an older, though little used, sentiment; a text written in c.1067, shortly after Edward the Confessor’s death and the Norman Conquest, ‘Vita Ædwardi Regis’ describes him as:

‘…anglorum Edwardo regi sancto nominis huius tercio revelata fuit…’

(St. Edward, king of the english, the third of this name)

By this system of numbering, Edward III would become Edward VI; but, evidently, that didn’t happen.

So why was there a change between Edward I and Edward III; why did one acknowledge the pre-Conquest Edwards, whilst the other seemingly omitted them? Both Edwards were direct descendants of William the Conqueror, drawing their claim to the English throne from him; perhaps that is what Edward III was trying to emphasise this lineage. However, William the Conqueror established his claim to England as Edward the Confessor’s rightful successor. Furthermore, Edward the Confessor was a venerated and popular saint in England during this period – hence three kings named after him.

It is impossible to say what cultural shift took place that led to the change from claiming lineage from the Anglo-Saxon kings, to defining the dynasty by the Conquest. Perhaps it was that Edward III was a child king, so they referenced the Conquest to project martial strength. We just can’t say.

This form ‘the xth after the conquest’ became very common during Edward III’s reign, and was continued by all his successors to varying extents, with some variations, such as ‘xth of that name after the conquest.’ Thus, we have ‘Richard the second after the conquest,’ and Henry, fourth of that name after the conquest,’ etc. It wasn’t until a 16th century king that the number, given in Roman numerals, was incorporated into the regnal name, forming the familiar Henry VIII.

Eventually, the ‘after the conquest’ suffix was dropped. This method of labelling our kings and queens was and continues to be retrospectively, anachronistically (though usefully) applied to all monarchs since the Conquest. The difficulties this created after the union of England and Scotland is a story for another time. But it has led us to our new king, Charles III.