In 1191, King Richard I of England married Berengaria, the daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. Theirs was one of the more unusual royal weddings in English history.

It was a good match for both of them; Berengaria, a princess from a small yet significant Spanish kingdom became the consort of the ruler of the vast Angevin empire, whilst Richard shored up support on the southern border of his empire, particularly against Aquitaine’s enemy, the counts of Toulouse.

By the time the marriage negotiations had been completed, Richard was about to depart for the Holy Land, in order to fight Salah al-Din and reclaim Jerusalem in what would later become called the Third Crusade (see my post about the word ‘crusade’ here), and was clearly unwilling to delay his plans. Instead, his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, by this time around 69 years of age, was sent to escort the young Berengaria from Navarre to Sicily, where they rendezvoused with Richard. Unfortunately, Berengaria arrived in Sicily after Lent had begun; marriages could not be solemnised during Lent, so their wedding would have to wait.

Berengaria therefore continued with Richard to the Holy Land as an unmarried woman, chaperoned by Richard’s sister, Joan, who had been rescued from captivity in Sicily following the death of her husband, William II of Sicily (but that’s a story for another time). En route, Joan and Berengaria’s ship ran aground off the coast of Cyprus. When Isaac Comnenus, the Byzantine ruler of Cyprus, threatened Berengaria, Richard came to her rescue, quickly capturing Isaac and Cyprus, which he used as a base to convey supplies to the Holy Land.

Berengaria and Richard’s stay on Cyprus coincided with the end of Lent, and allowed them to be married. We have three main accounts of their wedding. Two, ‘Chronica magistri’ by Roger of Hoveden and ‘Chronicon de rebus gestis Ricardi Primi’ by Richard of Devizes, were written by contemporaries, whilst the third, ‘Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi’, was written by a canon in the 1220s. ‘Itinerarium’ is generally said to have been based on lost contemporary accounts; however, I believe that there is a striking enough similarity with the account in Roger of Hoveden’s ‘Chronica magistri’ to say that it was one of the main sources of information for at least the wedding. Roger of Hoveden’s account is the most reliable, as he actually accompanied Richard to the Holy Land, and therefore was probably present at the wedding.

Whilst Hoveden dates the wedding to the 4th May, he then states that it took place on the feast day of ‘Saints Nereus and Achilleus and the martyrs of Pancratius,’ which is on the 12th May; Devizes also places the wedding on ‘the festival of St. Pancras.’ Most historians agree that the 12th May is the most likely; though how and why a church minister would mistake the date of the saints’ feast day is unclear.

Berengaria and Richard were married at Limassol, Cyprus by the king’s chaplain, Nicolas, who would later go on to be the bishop of Le Mans. Following the ceremony, Berengaria was crowned Queen of England, also becoming the Duchess of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, (newly) Lady of Cyprus, and Countess of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes.

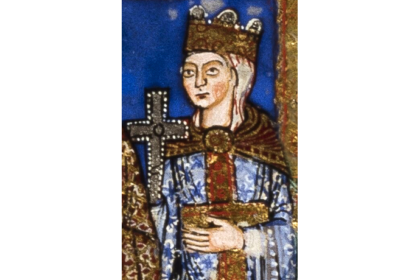

Along with these illustrious titles, Berengaria holds two other titles; she is the only Queen of England not crowned in England, and the only one never to set foot in England – at least whilst queen. After her return from the Holy Land, Berengaria resided in Richard’s French territories. There is some evidence that suggests she visited England after Richard’s death, and she may have been present when St Thomas Becket’s remains were translated at Canterbury in 1220. She eventually entered the monastic life in Le Mans, dying there in 1230. A tomb and remains believed to be Berengaria’s can be found in L’Épau Abbey to this day.

I have included the three accounts of Berengaria and Richard’s wedding, as they each offer a slightly different perspective on this momentous event.

~

Roger of Hoveden’s ‘Chronica magistri’ – c.1201

But in the month of May, the 4th that same month, on Sunday, the feast of Saints Nereus and Achilleus and the martyrs of Pancratius; Berengera, the daughter of the king of Navarre, was married to Richard, king of the English, on the island of Cyprus at Limeszun, Nicholas, the king’s chaplain, performing the office of that sacrament: and on the same day the king caused her to be crowned and consecrated as queen of England, by John the bishop of Ebroicense, and administering to him in that office, the archbishop of Bordeaux and the bishops of Évreux and Bayonne.

~

‘Chronicon de rebus gestis Ricardi Primi’ by Richard of Devizes – c.1192

And because Lent had already passed, and the lawful time of contract was come, he caused Berengaria, daughter of the king of Navarre, whom his mother had brought to him in Lent, to be affianced to him in the island.

~

‘Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi’ – c.1220

Chapter XXXV. — Of the nuptials of King Richard and Berengaria, and on the arrival of the king’s galleys.

On the morrow, viz. on the Sunday, which was the festival of St. Pancras, the marriage of King Richard and Berengaria, the daughter of the king of Navarre, was solemnised at Limozin: she was a damsel of the greatest prudence and most accomplished manners, and there she was crowned queen. There were present at the ceremony the archbishop, and the bishop of Evreux, and the bishop of Baneria, and many other chiefs and nobles. The king was glorious on this happy occasion, and cheerful to all, and shewed himself very jocose and affable.

The nuptials having been solemnly celebrated in a royal manner, one day all the king’s galleys, which had been anxiously looked for, arrived in port: they were equipped and defended with splendid armouries, and no one ever saw better or safer ships; and he added to them the five galleys which he had taken from the emperor. The king had thus forty armed galleys and sixty others of a very good quality.

~

Top image: Effigy believed to be Berengaria of Navarre in L’Épau Abbey