Despite the infamy of the case, Henry VIII was by no means the first king of England to seek a papal ruling on the invalidity of a marriage.

There is a very long, complex, but fascinating document preserved in the British Library. It is the records of a papal investigation and ruling on the validity of a marriage between Henry III and Joan of Ponthieu.

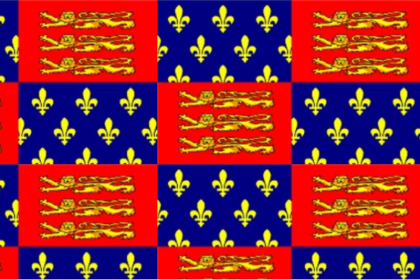

In 1235, Henry III sought to consolidate his position as king, provide an heir, and perhaps even create an alliance that would allow him to reclaim some of the Continental territory his father, King John, had lost.

There was one prospect which almost gave us a Queen Joan-the daughter of the count of Ponthieu. This region of France was close to Normandy, making it strategically desirable if Henry attempted to reclaim the lost duchy.

The sources are not clear, but it seems that negotiations proceeded to the point that Henry and Eleanor plighted their troth to one another. Historian of medieval marital law, David d'Avray, believes that through proxies, their vows may have been made ‘verba de praesenti,’ which would make them fully married in the eyes of God.

Unfortunately, the very reasons that made Joan a desirable match for Henry, also alarmed the king of France, Louis VIII, who made it very clear that he would do all in his power to block such a marriage. This was no idle threat; a marriage between Henry and Joan was technically illegal because they were related within four degrees of consanguinity; they shared a great-great grandfather in Louis VI of France. This was not a serious impediment, but it would require a papal dispensation. Such dispensation were granted all the time, and were fairly par for course in a period where most royal families were related to each other. However, the French threatened to lobby the pope to deny a dispensation; the proximity of France to Italy made annoying the King of England the lesser of two evils.

Another marriage prospect for Henry was also proposed around this time, Eleanor of Provence, who would bring an alliance with an important region of Southern France. In the face of the French opposition and an equally desirable, uncontested option, Henry backed down and chose to pursue a marriage with Eleanor of Provence. Their wedding took place on the 14th January, 1236, and by many accounts, they had a fairly happy and successful marriage. The vow, whatever form they took, to Joan of Ponthieu was forgotten, and in October 1237, Joan married the King of Castile.

More than a decade later, in 1249, Henry III started putting together an appeal to Pope Innocent IV to have his plight troth to Joan declared invalid due to consanguinity, and his marriage to Eleanor of Provence declared valid. It is unclear why precisely he chose this moment to pursue an official declaration on the matter. Perhaps there were rumours about his children by Eleanor being illegitimate. Henry and Eleanor’s eldest son and heir, Edward, turned 10 in June 1249, and around this time was granted lordship of Gascony. Perhaps it was in anticipation of starting the search for a wife for his son that motivated Henry to ensure none could doubt Edward’s legitimacy. We cannot know for sure.

Regardless, a full, formal investigation was pursued. Though it seems unlikely that the pope would rule that Henry and Joan had been, and were still, legally married, due to the turmoil it would wreck on both England and Castile, it seems that the commissioners conducted a proper and thorough investigation, interviewing many witnesses, and even sending a summons to the Queen of Castile to appear at the trial; Joan sent word that all knew that they were related within the forbidden degree, she did not contest the claim, but that she would not appear or act any further in the matter.

In 1252, the trial took place in Sens, headed by the bishop of Hereford upon the authority of the pope. Thirteen witnesses were summoned to attest to their known genealogies. By the end, the outcome was clear: Henry’s plight troth to Joan was invalid due to consanguinity, and his marriage to Eleanor was valid.

This outcome was formally confirmed in a letter in 1254 from Innocent IV, to which was attached a full report of the evidence and findings of the trial.

The story came full circle later that same year, as on the 1st November young Prince Edward was married to Eleanor of Castile, the daughter of Joan. Though we have no evidence, it was perhaps in anticipation of this match that Henry sought the papal ruling, to ensure no-one could accuse Edward and Eleanor of being siblings under canon law.

Below is the formal letter Pope Innocent IV sent, outlining the issues and declaring the findings on Henry’s two marriages.

Innocent, bishop, servant of the servants of God, to his most dear son in Christ H., the illustrious king of England, health and apostolic benediction. It is fitting for us to grant consent easily to the just desires of petitioners, and to ensure that the desired effect follows wishes that do no diverge from the path of reason. Therefore, since the world has grown old in corruption, and many people not only presume the worst in matters of which they are ignorant, but do not even hesitate to misrepresent as evil things they know without doubt to be good, you, prudently bearing this in mind, and desiring to make sure that calumnies of any jealous men should not in the future become linked to your children, humbly implored us some time ago to take care to provide for your honour and that of your children by our paternal solicitude, concerning the fact that you had sworn to marry our most dear daughter in Christ Joan the illustrious queen of Castile - the daughter of the Count of Pontieu at that time - who was then single, and that you thought fit to contract a marriage with her insofar as it was in your power, and finally, after finding that you were related to her in the fourth degree of consanguinity, when this marriage had by no means been consummated, you joined yourself in matrimony in the sight of the Church ou most dear daughter in Christ Eleanor, the illustrious queen of England, daughter of the count of Provence of famous memory. But when we had entrusted our letters in mandate form to our venerable brothers N. the Archbishop of York and N. the bishop of Hereford that they should inquire diligently into the truth of the matter, and make sure to declare by apostolic authority, if this is what they decided was the right verdict, that the first marriage and the oath you swore to contract this first one do not hold good, and the second one is valid, and curbing by ecclesiastical censure anyone who contradicts them, without the possibility of appeal: in the end, after the Archbishop had excused himself legitimately by his letter because he was unable to to take part in the cognizance of this matter, the same bishop proceeded with this matter alone, as our letter allowed him to do, and, when the parties had been summoned, and the aforesaid Queen of Castile replied that she was related to you in the aforesaid degree of consanguinity, and that she would not send anyone to defend this case, and would not come, nor involve herself in it, and finally neither appeared in person nor through a representative, he [i.e. the bishop of Hereford], in the presence of you proctor, after taking cognizance of the merits of the same case, and observing the order of law, with the counsel of prudent men, pronounced as his sentence that the marriage between you and the aforesaid Queen of Castile had been null, because of the impediment of your relationship of consanguinity in the fourth degree with her, and that the marriage contracted between you and the aforesaid E. the Queen of England was legitimate, notwithstanding the oath you swore to contract the first one, just as is contained more fully in the letter written at the hearing.

Therefore we, after inspecting diligently the proceedings of the aforesaid bishop and the sentence, approving the same sentence, and making good from our plenitude of power any defect, if there should be one, and regarding the same sentence to be ratified and pleasing: acceding to your requests, we confirm by apostolic authority and strengthen by the protection of the present document the sentence together with the aforesaid proceedings.