This portrait is part of a very interesting chapter in the history and historiography of the eternally controversial Richard III.

When discussing the appearance of an historical figure, the first thing people look for are photos and paintings of them. Sadly, no contemporary portraits of Richard III survive. This one, held by the Royal Collection Trust, is the closest we can get, and it seems to have been the model for nearly all extant portraits of Richard. Painted between 1504 and 1520, it portrays Richard with a rather bitter visage – narrowed eyes, thinned mouth, and of course, the hunched shoulders. Despite being painted upwards of 20 years after Richard’s death, it is very likely that the artist used a lost contemporary original or sketch as guidance.

It should be noted that the lead osteologist involved with the Leicester discovery of Richard III’s remains asserted that whilst Richard did have a significant, and painful, scoliosis, it would not have been barely noticeable under clothing, and clearly did not interfere with his activities as a militant, medieval king. The condition was so slight that no contemporary eye-witnesses bothered to mention it, and it is highly unlikely that any contemporary portraits of him whilst king would have included it – flattery was part and parcel of life for a royal portrait painter.

Research in 1970s and then in 2016 have shown that the figure we see in the portrait today is subtly, but distinctly, different from the one the artist originally painted.

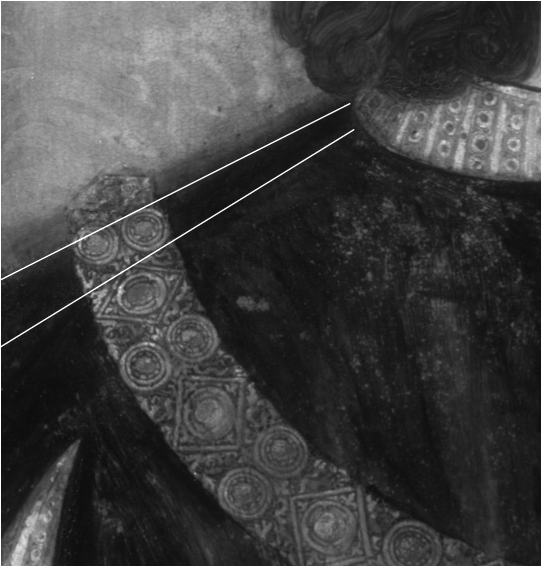

In 1973, an x-ray was taken on the portrait, which revealed that the artist had originally given Richard more full, less narrowed eyes, and that the line of Richard’s right shoulder had not originally been raised in the hunch that is visible in the portrait today.

Infrared reflectography was used in 2016 to show the charcoal sketch the artist originally made. This sketch confirmed the findings of the 1973 x-ray, but also showed many more extensive changes. At some point, Richard’s nose had been shortened, the mouth had been narrowed and compressed, and the entire length of his face was shortened. The lines of both shoulders were moved to accommodate this, but the right one significantly more so. The overall effect was to show a more deformed, mean looking man.

When were these changes made, and why? Analysis of the paint works suggests that the changes were made whilst the artist was still working on it. This portrait was commissioned for Henry VIII’s court, so it would have needed approval from the powers that be. This was a time when it was believed that outward appearance was a reflection of the state of your soul – a beautiful face meant a beautiful soul, and likewise, someone ‘deformed’ was a sinful, hell-bound soul. What most historians believe happened is that the artist began by making an accurate copy of the lost original, but then was ordered to make the changes to fit the Tudor narrative of the evil, deformed usurper; the portrait is uncannily similar to Polydore Vergil description in his ‘Historia Anglia’, which he was commissioned to write by Henry VII as a justification for the latter’s reign:

‘He was puny in stature and deformed of body, with one shoulder higher than the other; he had a short face with an expression that was harsh and cruel…’

So what does this mean for Richard? Well, it tells us that the Tudors were committed to the narrative of the evil, embittered, deformed king. It also tells us that we cannot trust any of the extant portrait of Richard, since they were all based upon this one. We still have wonderful written accounts, and of course, the facial reconstruction which was made based on Richard’s skeletal remains.