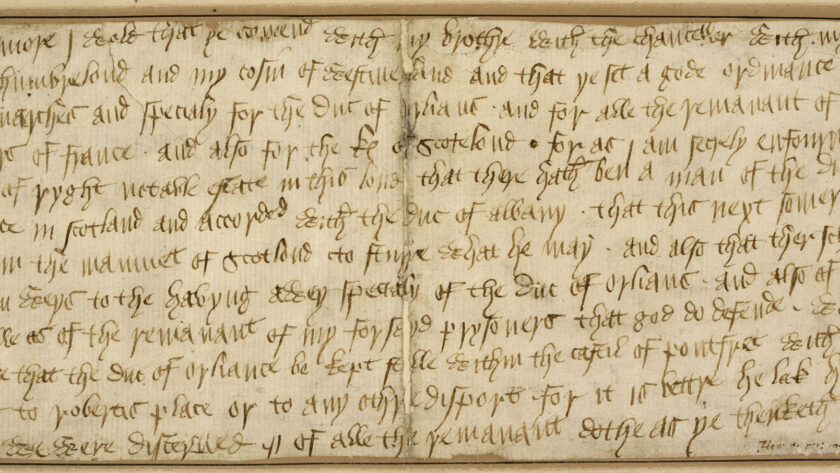

Above: Henry V’s own handwritten letter in English.

This letter, addressed to his regent, discusses the situation in the north of England and gives instructions on the Duc d’Orléans imprisoned at Pontefract Castle.

I was recently re-reading one of my favourite historical fiction novels, ‘Devil’s Brood,’ about Henry II and his tumultuous family, by the wonderful Sharon Penman. I always have to remind myself, though, that despite the English dialogue on the pages, none of these people would have spoken any form of English. After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the nobility of England all spoke Anglo-Norman, a form of medieval French, for many centuries. The medieval forms of English – Old English, which lasted until the mid 12th century, when it evolved into Middle English – were slow to be accepted by the courts of the English kings. But we can see how across the 14th and 15th centuries English became the language of kings.

Edward III was the first English king to recognise the importance of the English language, and to encourage its use. In 1362, Parliament was opened with an address by the Chancellor in English, rather than Anglo-Norman. Sadly the text of Chancellor William Edington’s speech does not survive, though it is likely that it began something along the lines of: ‘For the worship and honour of God, King Edward has summoned his Prelates, Dukes, Earls, Barons, and other Lords of his realm to his Parliament…’

This Parliament was also significant in the history of English because of a piece of legislation it passed: the Pleading in English Act (1362). The statute recognised that English was the ‘Tongue of the Country.’ It was also a recognition of the importance for everyone to be able to understand the laws of the land and court proceedings. The modernised text of the statute reads:

‘Because it is often showed to the King by the Prelates, Dukes, Earls, Barons, and all the Commonalty, of the great Mischeifs which have happened to divers of the Realm, because the Laws, Customs, and Statutes of this Realm be not commonly holden and kept in the same Realm, for that they be pleaded, stewed, and judged in the French Tongue, which is much unknown in the said Realm; so that the People which doe implead, or be imploded, in the King’s Court, and in the Courts of other, have no Knowledge nor Understanding of that which is said for them or against them by their Serjeants and other Pleaders; and that reasonably by the said Laws and Customs and known, and better understood in the Tongue used in the said Realm, and by so much every Man of the said Realm may the better govern himself without offending the Law, and the better keep, save, and defend his Heritage and Possessions; and in divers Regions and Countries, where the Kin, the Nobles, and other of the said Realm have been, good Governance and full Right is done to every Person, because that their Laws and Customs be learned and used in the Tongue of the Country: The King, desiring the good Governance and Tranquility of his People, and to put out and eschew the Harms and Mischiefs which do or may happen in this Behalf by the Occasions aforesaid, hath ordained and stabilised by the Assent aforesaid, that the Pleas which shall be pleaded in any Courts whatsoever, before any of his Justices whatsoever, or in his other Places, or before any of his other Ministers whatsoever or in the Courts and Places of any other Lords whatsoever within the Realm, shall be pleaded, shewed, defended, answered, debated, and judged in the English language, and that they be entered and inrolled in Latin’

~

Edward III’s grandson and successor, Richard II, was almost certainly fluent in English, though it still would not have been his first language. It was actually one of Edward III’s younger sons, John of Gaunt, who would play a significant role in shaping the language of the court.

John was a great patron of the arts, especially poetry and literature. He was the brother-in-law and patron of the great Geoffrey Chaucer, author of ‘The Canterbury Tales.’ John was heavily involved in the development of English literature and language, and as such, he raised his son, the future Henry IV, to be the first English native speaker within the royal family. Henry had come to the throne by controversial means – he had overthrown his cousin, Richard II. To emphasise his own claim to the throne of England, and to show that he was in-touch with the people he sought to rule, he made use of the English language; Henry IV’s speech at his coronation in 1399 was the first time English had been used by a monarch since the Norman Conquest of 1066.

‘In the name of Fadir, Son, and Holy Gost, I, Henry of Lancaster chalenge this rewme of Yngland and the corone with all the members and the appurtenances, als I that am disendit be right lyne of the blonde coming fro the gude lorde King Henry Therde, and thorghe that ryght that God of his grace hath sent me, with the helpe of my kyn and of my friends, to recover it – the whiche rewme was in poynt to be undone for defaut of governance and undoing of the gode lawes.’

~

There is little evidence of Henry IV using the English language for any other official purposes as king. It was his son, Henry V, who promoted English as the language of his court and government; Chancery Standard English became the language of official documents, and government records began to be kept in English. Henry V even issued his own personal instructions in English.

So with the efforts of Edward III, Henry IV and Henry V, English, after many centuries, once more became the language of English kings.