In 2019, I wrote a university thesis about concepts of history, change, and time in the 15th and 16th centuries. Part of this thesis included a section on John Foxe, and his division of history in his famous book ‘Actes and Monuments,’ sometimes called ‘Book of Martyrs.’ Foxe wrote 4 editions of this book; the version discussed here is the 1570 edition. This is a fascinating area, and gives an interesting look at how people of the Tudor period were thinking of history and their place within it. This is an adapted version of my section of John Foxe – I hope you enjoy.

~

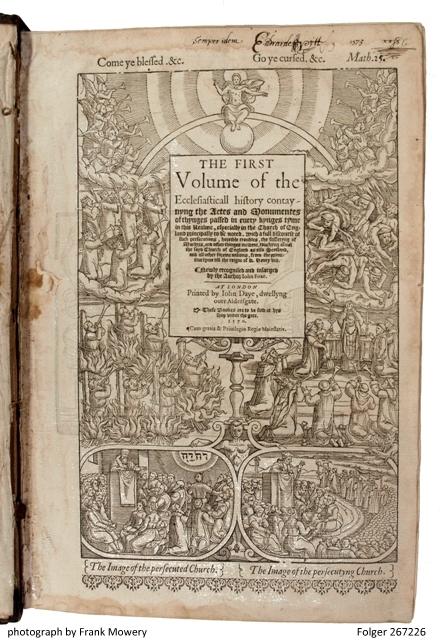

Born in Lincolnshire in 1517, John Foxe was an English Protestant cleric, martyrologist, and historian. During Mary I’s Catholic regime (1553-1558), Foxe went into exile in the German states and Austria, where he was heavily involved with John Knox and his faction, and wrote a precursor to ‘Actes and Monuments,’ about the history of persecutions within the Church. Six months after Elizabeth I’s ascension in 1558, Foxe returned to England, and became a prolific writer and leader of the Church of England. He began writing ‘Actes and Monuments’ after his return to England, inspired and partially based on other writings he had begun on the Continent. Included in the text is a history of the development of the Christian church, and a martyrology, particularly recounting the martyrs of the Protestant cause within his own lifetime. Foxe wrote the book for the purpose of justifying the Protestant schism and condemning Roman Catholicism; in doing so, Foxe used history to fit his vision: he frames Anne Boleyn as a Protestant martyr, though the general consensus amongst modern historians is that she died for her Francophilia, not her Protestant leanings. ‘Actes and Monuments’ is an incredibly important text for many reasons, including its insight into how history was being thought of by sixteenth century people.

The sixteenth century conception of history was based upon the works of Augstine (354-430), who is believed to have begun a tradition of the Six Ages of the World in his ‘De catechizandis rudibus,’ dividing the past into five ages – i. Adam to Noah; ii. Noah to Abraham’ iii. Abraham to David; iv. David to the Babylonian captivity; and v. from the Babylonian captivity to Christ – with the present era being the sixth, dating from Christ, and presumably ending with the Second Coming. This schema was frequently used in medieval historiography, either with adherence to Augustine’s form, or adapted to fit the purpose or vision of the author, including by influential chroniclers such as Isidore of Seville and the Venerable Bede. This method of dividing time continued to be used and adapted down the centuries, sometimes with additional eras, or different methods of dating. In ‘Actes and Monuments,’ Foxe sets out a formal periodisation of the Church from the time of Christ to the present. There is no reason to believe that Foxe was discounting the Augustinian model; it perhaps can be said that Foxe was dividing Augustine’s sixth age into smaller subsections.

For Foxe, history was an ongoing process of transition from one ‘age’ to another, which continued on through his own time. Foxe projected his own experiences with the English Reformation onto the past. He imposed his own neat periodisation onto the past, characterising each ‘age’ in a way which supported his pro-Reformation beliefs.

In the first few pages of the first Book, which act as a prologue, Foxe states his intention and reason for his conception of the history of the Church:

‘I haue here purposed (by the fauourable grace of Christ our Lord) in this history to digest & compile…so that in these reformed daies, we…may therfore poure out more aboūdant thankes to the Lord for this his so sweete and mercyful reformation.

For the better accomplishing wherof, so to prosecute the matter, as may best serue to the profit of the reader, I haue thought good first…to comprehende or runne ouer the whole state and course of the Church in general, in such order and sort, that diuiding and digesting the whole tractation of this historye, in to fiue sundry diuersities of times.’

~

Foxe’s Ages of the Church:

– The first age of the Church was characterised as the time of the apostles, ‘suffering’ and ‘martyrs’, lasting ‘from the Apostles age about 300 yeares.’ Although this seems to suggest dating the first age of the Church from the death of Christ, the later divisions imply that Foxe meant dating from the end of the Apostolic Age, with the death of the last Apostle, John, in 100 A.D., which would mean that this era ended in c.400 A.D.

– The second age was the ‘flourishing time’ of the Church, when the Church was still pure and being spread from the Middle East, throughout Europe, ‘which lasted o-ther 300 yeares,’ from 400 – 700 A.D.

– The third age of the Church was a period of ‘the declining or backeslyding time of the Church,’ characterised by ‘hypocricy…ambition and pride,’ which ‘comprehendeth other 300 yeares, vntil the loosing out of Sathan, which was about the thousand yeare after Christ.’ In discussing this period of time, from 700 A.D to 1000 A.D., John Foxe becomes the first person to use the phrase ‘middle age’ in English.

– The fourth age was the time of the ‘loosing out of Sathan’ around the year 1000A.D. and marked the beginning of ‘the time of Antichrist, or the desolation of the Churche.’ In this time the ‘Antechrist, raigning in the Church of God by violence and tiranny,’ led to a point whereby ‘both doctrine, and sincerity of life was vtterly almost extinguished, namely in the cheife heds and rulers of this west church.’ This association between the papacy and the Antichrist was increasingly popular from around 1300, when there was increasing dissatisfaction with the corruption of the Church. These depictions were usually associated with papal prophecies of an ‘apocalyptic angel-pope tasked with carrying out church reform.’ Although these types of prophesies were also common in sixteenth and early seventeenth century Reformation literature, Foxe was not offering a prediction of the future, despite the defeat of the Antichrist being associated with the Second Coming and Last Judgement, but rather was emphasising the importance and legitimacy of the English Reformation against Roman Catholicism, by placing it within the context of apocalyptic literature. According to Foxe, this time of the Antichrist lasted ‘400 yeares…til the time of Wickliffe and Iohn Husse.’

– At this point the fifth age began, in around 1400, which was the time of ‘the reformation and purging of the Churche of God.’ This age of reformation was characterised as:

‘…wherein Antichrst beginneth to be reueled, and to appeare in his coulours, and his antichristian doctrine to be detected, & the number of his church decreaseth, and the number of the true Church increaseth.’

Foxe’s idea of the age of reformation was a time of disassembling the corrupt Catholic Church and reassembling it in the form of the early, flourishing Church. Foxe believed that ‘the durance of which time…the Lord and gouernours of all times onely knoweth.’ For Foxe, this age was ongoing, potentially to end only with the Second Coming of Christ.

~

You can read more about John Foxe and the texts of his ‘Actes and Monuments’ here, on the Digital Humanities Institute website: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/foxe/index.php