When Catherine Howard’s sexual history prior to her marriage came to light in November 1541, it created a problem: legally speaking, she had not done anything wrong. Her sexual behaviour with Henry Mannox and Francis Dereham, whilst immoral by the standards of the Church of England, did not constitute a crime. Even the allegations of an affair with Thomas Culpeper whilst she was married to Henry VIII were problematic – all that could be proved was that they had met privately and in secret. Both parties denied that anything sexual had actually taken place, though Culpeper claimed that they both desired it. Everything else was innuendo. Even the letter that Catherine sent to Culpeper is vague, and in many ways was in keeping with the conventions of courtly language (you can read more about this letter in a post I made last year). Whilst rumour and the hint of impropriety in the letter were enough to condemn a relatively lowborn man like Culpeper, more definitive proof was needed to bring down a Queen.

Dereham claimed that he and Catherine had pledged themselves to a pre-contract to marry after Catherine’s guardian, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, had caught them together and banished Dereham. In the eyes of the Church and the law, a pre-contract was as good as a marriage, especially if it had been consummated. But there was no evidence to support a pre-contract between Dereham and Catherine, which isn’t unusual, as a pre-contract could be as simple as two people promising to marry, with no need of a priest, witness, or paperwork. Furthermore, Catherine vehemently denied it, claiming that Dereham had forced himself upon her. Whilst Dereham was found guilty of treason and executed, it was for a words he confessed to under torture: Dereham had apparently admitted that he had said he could ‘still marry the Queen if the King were dead,’ which was a treasonous utterance; in fact, it is very similar to the exchange between Anne Boleyn and Henry Norris, where she accused him of ‘look[ing] for dead men’s shoes, for if aught came to the King but good, you would look to have me.’ Regardless, the admission of imagining the King’s death did not involve Catherine, and the pre-contract was not technically a crime.

Even if the pre-contract argument could be used to dissolve Henry and Catherine’s marriage, it had been utilised far too recently in the Anne of Cleves annulment. Besides, that would once again only allow for the marriage to be annulled, and, there were only so many living former wives that Henry could be seen to have.

So though Henry felt humiliated and betrayed by the wife he had adored, did not have a simple legal recourse. Whilst lack of evidence had not posed any sort of problem in the indictment of Anne Boleyn – we can prove that the charges were trumped up, and that Anne and her co-accused were often not even in the same places on the days they were alleged to have consorted – another sham trial was not a good look.

Instead, Henry had a piece of legislation passed through Parliament that would make Catherine’s actions illegal. The full title of the legislation was ‘An Act concerning the Attainder of the late Queen Catherine and her Complices,’ but was shortened to the ‘Royal Assent by Commission Act 1541.’ In the 21st century most countries prohibit, to some degree, ‘ex post facto’ laws, i.e. laws that can be retroactively applied, but that principle of law did not exist in 16th century England. This Act essentially made it High Treason for anyone who was to marry the King or his descendants to conceal their past sexual history, or for anyone who knew of their history to conceal it.

The Act read:

‘Queen Katharine attainted of Treason, and her Complices ; and all their Lands and Tenements, Goods and Cattels shall be forfeit to the King. It shall be lawful for any of the King’s Subjects, if themselves do perfectly know, or by vehement presumption do perceive, any Will Act or Condition of Lightness of Body in her which shall be the Queen of this Realm, to disclose the same to the King, or some of this Council ; but they shall not openly blow it abroad, or whisper it, until it be divulged by the King or his Council. If the King, or any of his Successors, shall marry a Woman which was before incontinent, if she conceal the same, it shall be High Treason ; and so shall it be in any other knowing it, and not revealing it to the King or one of this Council, before the said Marriage or within twenty Days after. If the Queen or Wife of the Prince, shall by Writing Message Words Tokens or otherwise, move any other to have carnal Knowledge with them, or any others shall move either of them to that End, then in the Offender it shall be adjudged High Treason.

Be it declared by Authority of this present Parliament, That the King’s Royal Assent by his Letters Patent under his Great Seal, and signed with his Hand, declared and notified in his Absence to the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and to the Commons, assembled together in the high House, is and ever was of as good Strength and Force, as though the King’s Person had been there personally present, and had assented openly and publickly to the same.

And be it also enacted, That this Royal Assent, and all other Royal Assents hereafter to be so given by the Kings of this Realm, and notified as is aforesaid, shall be taken and reputed good and effectual to all Intents and Purposes, without Doubt or Ambiguity ; any Custom or Use to the contrary notwithstanding.’

~

It was a very neat, convenient little Act; along with setting out the illegality of concealing Catherine’s past sexual history, it was also attainted her. Essentially, the Act was the law, the judge, and the jury, all in one. Before it was passed, Catherine was offered a jury trial, which she declined, perhaps out of a sense of pride or shame. In the end, the Act passed on the 29th January, 1542, sealing her fate and that of Jane, Lady Rochford. Technically many of the Howard family members who had been taken into custody following Catherine’s arrest were also guilty, particularly the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, who admitted to promoting Catherine as a bride for the King in the full knowledge of her granddaughter’s past. However, the King’s Privy Council urged leniency, and most were released after a period of imprisonment.

Catherine and Jane were not so lucky. They were executed two weeks later, on the 13th February, 1542.

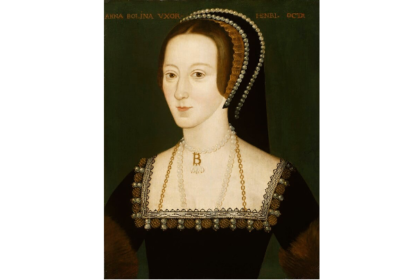

Top image: Portrait of a Young Woman, possibly Catherine Howard, by the workshop of Hans Holbein, said c. 1540-45.