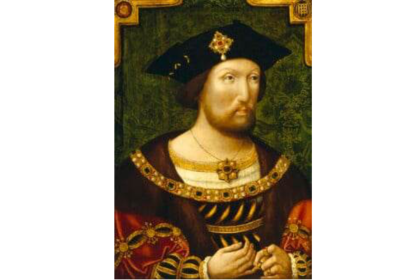

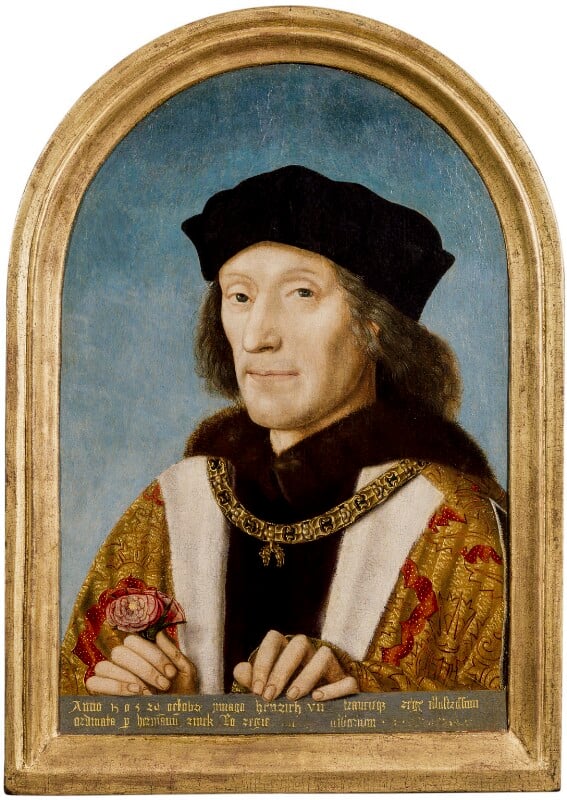

It can be difficult sometimes for historians to judge how the major events of the past impacted on the day-to-day lives of ordinary people. Henry VII’s ascension, for example, had an immense impact on the nobility of England; but to what degree was that felt by the common woman and man?

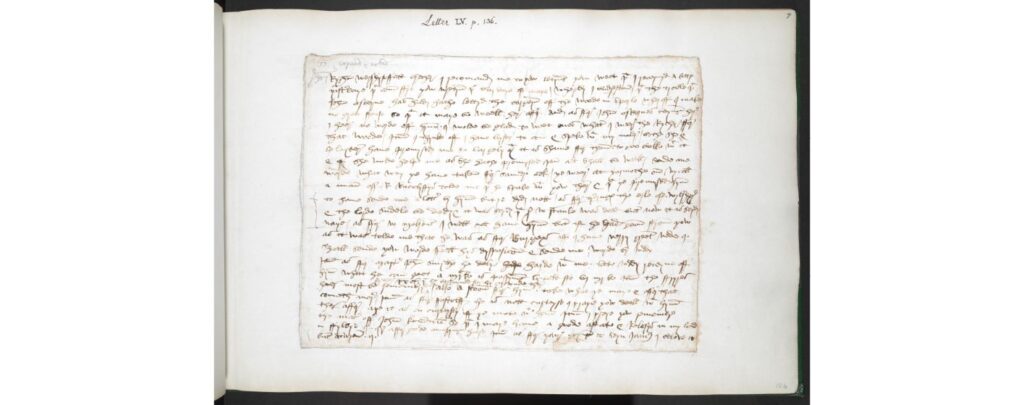

We do our best to uncover these attitudes by reading between the lines of letters and documents which have survived; as I’ve shown in previous posts, sometimes the smallest details in letters can be very revealing of social attitudes, behaviours, and feelings.

Even something as simple as the form of dating letters could be suggestive of how people viewed major events of their world. Including the day, month, and location of composition had been part of the codified form of letters since Antiquity, and though letter writing by this point was slightly less strictly structured, this was still an important element included in most letters in some form, including the Paston Letters. The Pastons were a gentry family living in Norfolk in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. A large corpus of their family letters from between 1422 and 1509 has survived and has been extensively studied as an invaluable source of information on the Wars of the Roses.

There are only two letters amongst the Paston collection which were written within a year of Richard III’s death and Henry VII’s victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field on the 22nd of August, 1485. The beginning of a new regime is acknowledged in both of these letters; in the sign-off, both authors state that they were written in the first year of Henry VII’s reign. The first is a draft letter written less than a month after the Battle of Bosworth Field, by Elizabeth Browne to her nephew John III Paston about the death of Elizabeth’s father back in 1444, which is concluded:

‘signed wyth myn hand, and sealid wyth my seale the xxiij daye of September the first yer of the reyngne of Kyng Herry the vijth.’

The second is a letter written at the beginning of 1486 by Margery Paston to John III Paston, about a number of everyday matters, such as the location of a ‘teppet of velvet,’ and some venison John had sent Margery, which is signed:

‘Wretyn at Castyr Hawill the xxj daye of Janeuer jn the furst yere of Kyng Harry the vijth.’

Dating by regnal year was a feature in many types of texts from this period; most official documents and chronicles used this method of dating, imposing a form of periodisation based on the reigning monarch. Nor was this a new development in epistolary style; though not as frequent in letters as in other official documents, in more formal letters it was not uncommon to include the regnal year in the signature; for example one letter, not from the Paston collection, written on 12th March, 1483 is signed ‘Wryttyn at Hurtton the xijth day of Marche, Ano xxiijo R. Ed. iiijti, By yure Cossyn Phllp. ffytz Lowys.’

This acknowledgement of regnal year, or even a new regime, however, does not appear anywhere else in the Paston Letters. Though there are many extant letters from 1461, when Edward IV ascended the throne; 1470 when Edward IV was deposed, and Henry VI was reinstated; 1471 when Edward IV was restored; and 1483 when first Edward V was declared king before being deposed in favour of Richard III, there are no formal acknowledgements or references to regnal years in the signatures. The fact that this style appears at this time is significant; that people felt the need to acknowledge the beginning of a new regime, even when that change was not the topic of the letter, shows just how momentous and extra-ordinary these events were perceived to be. This use of regnal year in the dating of these letters is a clear acknowledgement of a new era, and implicitly the end of an old one.

There are several possible reasons that Henry VII’s first regnal year was particularly noted in these letters. One is that Henry VII’s ascension marked the end of the Plantagenet dynasty and the beginning of the Tudor dynasty. This reason is not as strong, as the change in dynasty is not referred to, and Henry VII strongly emphasised his Plantagenet descent from Edward III, in order to establish the legitimacy of his claim to the throne. Another possible reason is that Henry VII’s victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field and subsequent ascension to the throne was viewed by the people of England as a decisive end to the uncertainty surrounding who had the right to the throne that had plagued the previous decades. Regardless of the reason, it remains clear that this was a moment which was regarded as a point of change significant enough to be acknowledged.