Inventory lists can reveal all sorts of details, such as when a portrait of Henry VIII appeared in a 16th century manuscript (you can read my post on that here).

The Folger Shakespeare Library holds many manuscripts relating to the reign of Elizabeth I. One of these is an inventory of Elizabeth’s wardrobe and jewels; it’s full title is:

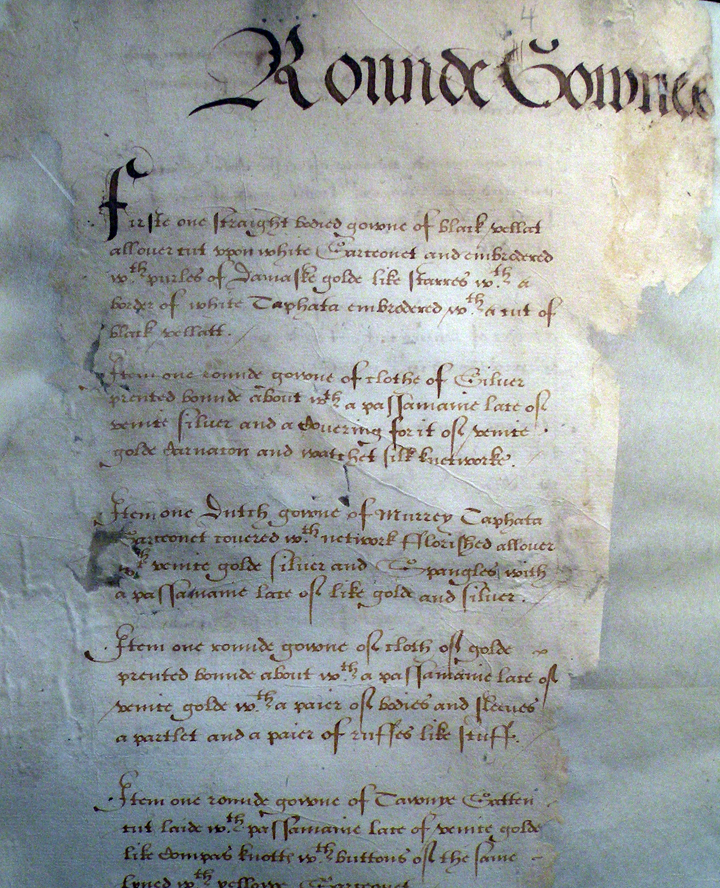

‘A Booke of all suche Robes apparell and garments remayninge with thoffice of her highnes warderobe of Robes. Serveied viewed and laid apart by vertue of her highness Comission under the greate Seale of Englande bearing date the iiiith daie of Julie in the said xliith yeare of her Majesties raigne and directed unto the right honorable Thomas Baron of Buckhurst Lorde highe Threasurer of Englande, George Baron of Hunsdon lorde Chamberlayn of her Majesties house, Sir John Fortescue knight Chauncellour of thexchequer and Sir John Stanhop knight Threasorer of her Maiesties Chamber. And alsoe of all suche Jewells and other parell as by the saide Comissioners are founde to bee loste by her Majestie and to be wantinge since the tyme that the saide Robes and Jewells have been comitted to the truse and Custodie of Sir Thomas Gorges knight’

If your eyes didn’t glaze over by the second line, you will have noticed that part of the inventory’s purpose was to list ‘all suche Jewells and other parell as by the saide Comissioners are founde to bee loste by her Majestie’

One item on the list caught my attention whilst perusing the inventory:

‘Firste one Button of golde with fine pearles in it loste from her Maiesties kirtle at a plaie at Richmonde at Xpmas 1595’

Though we obviously don’t know for certain exactly what the button looked like, I imagine it was something similar to the detail in the second image, taken from the Ditchley portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c.1592.

The ‘plaie at Richmonde at Xpmas 1595’ took place on Saturday, 27th December, and was put on by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. This was a company of actors founded in 1594 under the patronage of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, the Lord Chamberlain of England. This was the company that Shakespeare wrote for, with most of the leading roles being performed by Richard Burbage.

It isn’t clear what play was being performed during these Christmas festivities. ‘Richard II,’ ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ and ‘The Two Gentlemen of Verona’ by Shakespeare are believed to have been produced in 1595. There is also evidence that around this time the Lord Chamberlain’s Players put on performances of plays entitled ‘Edward III,’ ‘Locrine,’ and ‘Richard, Duke of York.’ I have been unable to pinpoint which play Elizabeth would have enjoyed, though I think it is unlikely that a play about Richard, Duke of York, who sought to overthrow a king, would be well-received, nor would Shakespeare’s ‘Richard II.’ which shows the replacement of a weak monarch with a younger, stronger king. Beyond this, we just can’t say for now.

Nor can we know what happened to Elizabeth’s lost button. Was it kicked about underfoot, to be lost until a keen metal detectorist uncovers it? Or was it found by a lowly servant, who secreted it away, to be kept as a treasured souvenier, or pawned to improve their and their family’s lot in life.

Top image: the Ditchley portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c.1592