England and France are renowned for their historic rivalry; a French author put it best when he described England as ‘our most dear enemies.’ One of the sources of this tension was the English claim to the throne of France, which began in the 14th century.

Although the monarchs of the United Kingdom of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland have long since ceded their historic claim to the throne of France, vestiges of this claim still remain in the current monarchy and coronation. In fact, the emblem of France and the French monarchy, the fleur de lys, was displayed in a prominent position, and yet remained overlooked, during King Charles III’s coronation.

To understand where and why the symbol of French monarchy will be in a British coronation, we need to go back to the 14th century.

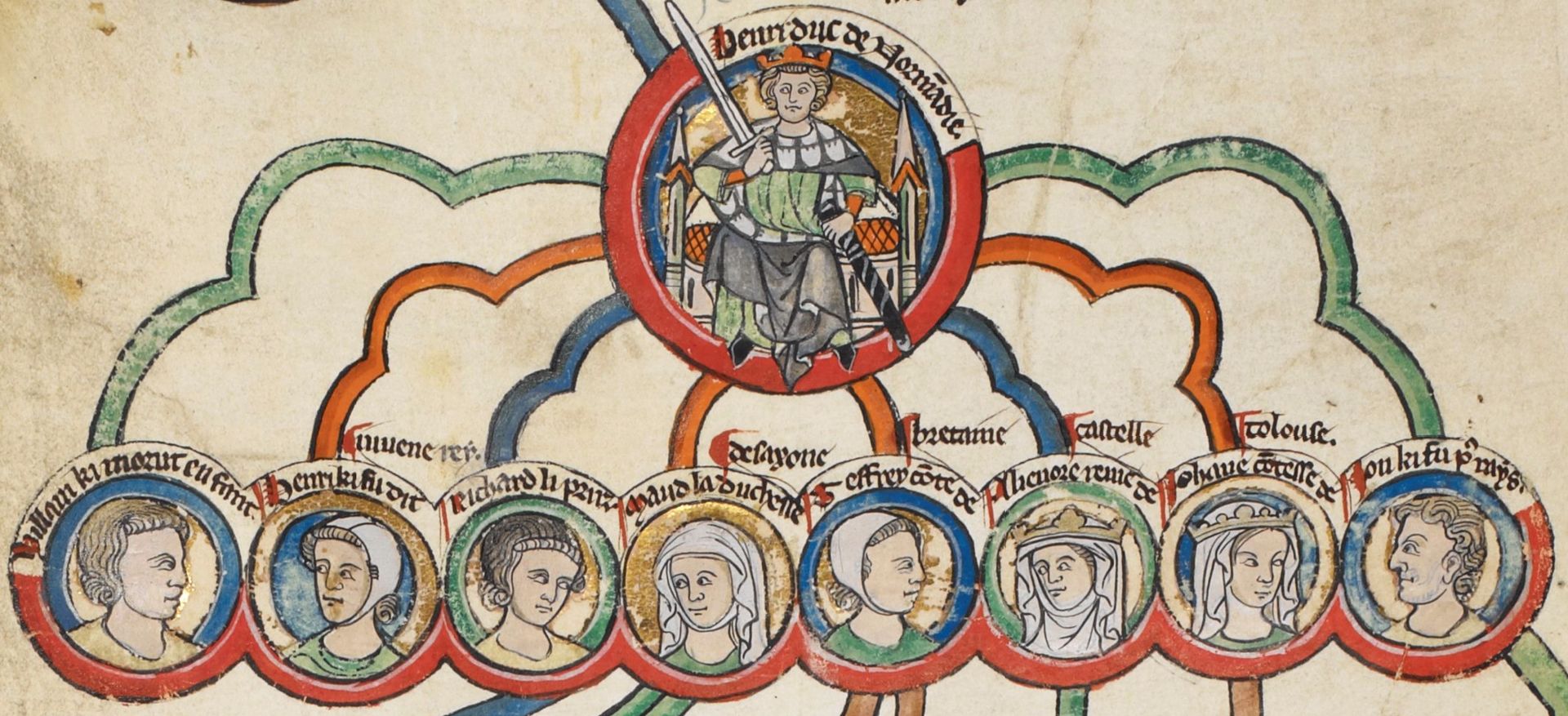

England’s claim to the French throne dates back to Edward III who, in 1328, claimed the title after the death of his maternal uncle, Charles IV. Edward was the nearest living male blood relative of Charles; however, his claim came through his mother. This was the first time in many centuries that a King of France had died without a son to succeed him, and this was used to claim a precedent of agnatic succession, i.e., the crown passing down only through the male line. In reality, the French preferred a more distantly related successor than an English one. Instead of Edward, the French throne passed to Charles’ cousin, who became Philip VI. Although Edward did initially pay homage to Philip for the Duchy of Aquitaine, thereby acknowledging him as King of France, by 1340, Philip VI had confiscated Aquitaine, prompting Edward to officially claim the title—this exchange of hostilities would become the Hundred Years’ War.

Every English and British monarch thereafter included King or Queen of France in their titles, although Henry VI was the only one who was crowned and recognised in France as such, up until George III. This was despite multiple treaties which technically put an end to England’s claim to France.

Edward III himself did actually renounce the title in 1360 with the Treaty of Brétigny; however, with the resumption of hostilities in 1369, Edward resumed the title and his claim.

The Treaty of Troyes, one of Henry V’s greatest achievements, saw him recognised as the heir to the throne of France; although he did not live to ascend that throne himself, his infant son, Henry VI, was crowned King of France on the 16th December, 1431. Many in France were unhappy with this, and by 1453, the only area of France under English rule was Calais.

Nevertheless, the title endured, even after the Treaty of Picquigny, which saw Edward IV promise to not pursue his claim to France.

Henry VIII managed to capture some small areas of France, but was unable to hold them for long. His daughter, Mary I, would lose even Calais in 1558. Although Elizabeth attempted to reclaim Calais, and was able to capture Le Havre in 1561, the Treaty of Troyes in 1564 confirmed the complete loss of French territories under English rule.

It wasn’t until 1800, with the Act of Union which saw the Kingdom of Great Britain join with the Kingdom of Ireland, that George III chose to drop the claim to the French throne; given that the French Revolution had seen to the annihilation of a French monarchy, there seemed little point in maintaining it.

Along with the title, came the heraldry. The fleur de lys had been used as the symbol of the French monarchy since at least the 12th century, although 13th and 14th century allegories claim that it had its origins as far back as the first king of the Franks, Clovis I, in the 5th century. Louis VI is the earliest king we have evidence of using the fleur de lys as a royal emblem. By 1211, it was definitely used as a heraldic symbol, and around this time became part of the Royal Coat of Arms of France. The French Revolution saw the end of the heraldic fleur de lys in France.

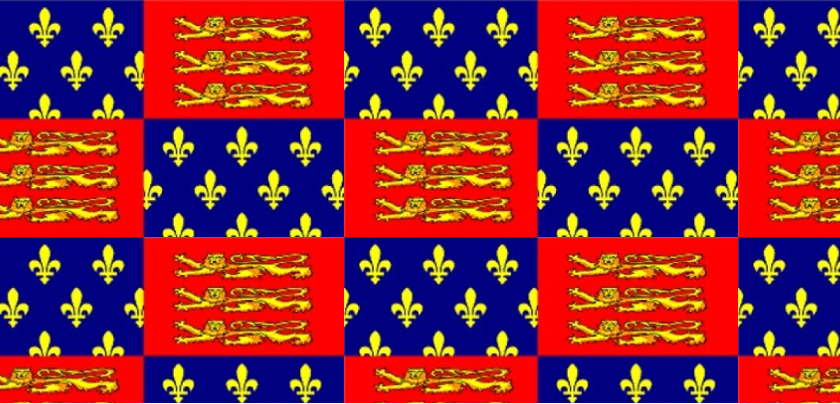

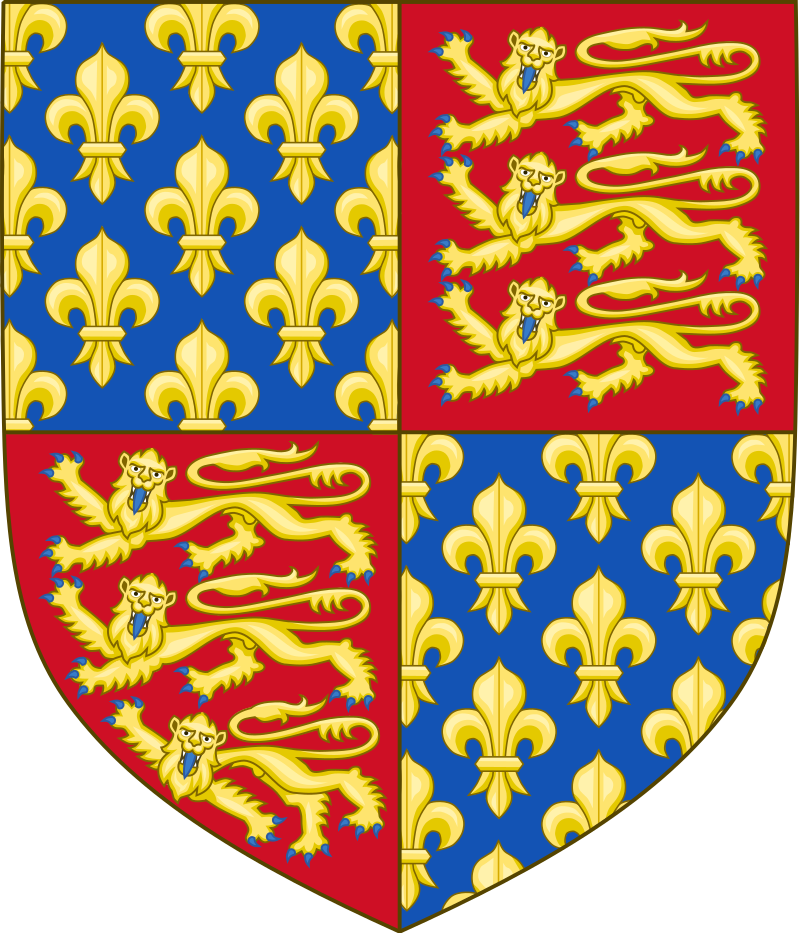

When Edward III claimed the kingship of France, he quartered the Royal Coat of Arms of England with those of France to reflect the dual kingship he was claiming. In different forms, the fleur de lys remained a significant part of the royal arms of England, and then the Royal Arms of Great Britain, until George III renounced the claim, and the four quarters of the arms were changed to represent each of the three cultural identities within the United Kingdom (sorry Wales) – the gold lions of England, the red lion of Scotland, and the harp of Ireland. Interestingly, the one gap in usage was during Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth, 1649-1660, however it was quickly revived when the monarchy was restored.

Coats of arms are not the only place that heraldic emblems appear. If you saw my article on the depictions of medieval and Tudor coronations, you will have noticed that from Richard III onwards, the kings and queen of England wore crowns that had the fleur de lys as a significant component. Due to the nature of these illustrations and portraits, it is difficult to identify these crowns, or even how many separate crowns we are talking about. None of these crowns survived Oliver Cromwell’s destruction of the crown jewels; nor did the crown of St. Edward the Confessor, one of the most significant relics of the monarchy.

When St. Edward’s Crown was remade after the restoration, the design was modified—the baroque arches, for examples—but it is difficult to know whether the fleur de lys were added at this time as a nod to the Tudor Crown and other medieval crowns, or whether they had been added to the original crown of St. Edward by an earlier monarch.

Nevertheless, the fleur de lys are such a prominent and important symbol on St. Edward’s Crown that many crowns that have been made since then for the British monarchy, and even since George III’s renunciation of the French claim, still include them. Thus, not only will King Charles III be crowned with fleur de lys when St. Edward’s Crown is placed on his head, but he will also display it when he wears the Imperial State Crown as he leaves the Abbey. Queen Mary’s Crown, which was created in 1911, will be used by Queen Camilla; this crown also has prominent fleur de lys. It seems that King Charles will also have two Armills, bracelets of gold and enamel, placed on his wrists during the ceremony, as symbols of knighthood and leadership, which also have fleur de lys on them.

One further thing to note; although the fleur de lys was removed from the shield of the Royal Coats of Arms in 1800, it does still have a presence today; the crown at the top of heraldic achievement, and the crowns on the lions (and unicorn, if you are in Scotland) was St Edward’s Crown, and is now the Tudor Crown (as per Charles III’s cypher), and the fleur de lys can be made out on close inspection. It can also be seen around the neck of the unicorn.

Of course today, the fleur de lys symbol is merely part of traditional heraldry, and does not indicate a claim to the throne of France. Still, it is interesting to see how the fractious history of England and France continues to shape the symbols of the United Kingdom.