Writing a decade later, Gervase of Canterbury recounted an extraordinary astronomical event that had been witnessed by a group of his fellow monks on the 18th June, 1178:

This year, on the Sunday before the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist, after sunset, a wonderful sign appeared; five or more men sitting on the opposite side. For the new Moon was bright, stretching out its horns towards the east, after the manner of its newness; and behold, suddenly the upper horn was divided in two. From the midst of this division sprang a burning torch, throwing forth flame, coals, and sparks. Meanwhile the body of the Moon which was below was tormented as if anxious, and, to use the words of those who reported this to me and saw it with their own eyes, the Moon throbbed like a snake stricken. After this it returned to his proper state. It repeated this change a dozen times and more, that is to say, that the fire might withstand the various cannons as it had been prescribed, and return again to its former state. After these vicissitudes, from horn to horn, that is to say, it became semi-black for a long time. Those men who saw this with their own eyes reported these things to me who write these things, ready to give their faith or to swear, that they added nothing to the aforesaid falsehood.

(Hoc anno, die Dominica ante Nativitatem Sancti Johannis Baptistae, post solis occasum, luna prima, signum apparuit mirabile, quinque vel eo amplius viris ex adverso sedentibus. Nam nova luna lucida erat, novitatis suae more cornua protendens ad orientem; et ecce subito superius cornu in duo divisum est. Ex hujus divisionis medio prosilivit fax ardens, flammam, carbones et scintillas longius proiciens. Corpus interim lunae quod inferius erat torquebatur quasi anxie, et, ut eorum verbis utar, qui hoc michi retulerunt et oculis viderunt propriis, ut percussus coluber luna palpitabat. Post hoc rediit in proprium statum. Hanc vicissitudinem duodecies et eo amplius repetiit, videlicet ut ignis tormenta varia sicut praelibatum est sustineret, iterumque in statum rediret priorem. Post has itaque vicissitudines, a cornu usque in cornu scilicet per longum seminigra facta est. Haec michi qui haec scribo retulerunt viri illi qui suis hoc viderunt oculis, fidem suam vel jusjurandum dare parati, quod in supradictis nichil addiderunt falsitatis)

Gervase, born c.1141, was a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury, and was amongst those who served St Thomas Becket and helped bury him. He was also a chronicler, writing a number of regnal and ecclesiastical histories.

Whilst Gervase did recount stories and visions for rhetorical and political purposes (the most egregious example being a vision he claimed to have of the sainted Thomas Becket driving out an Archbishop who had angered Gervase), the account of this lunar event is not ascribed any particular meaning, nor does it appear within the context of larger events of disputes. Gervase was very interested in observing heavenly bodies, often describing eclipses. So as fanciful as his description may appear, it should not be discounted as fancifulness or rhetoric.

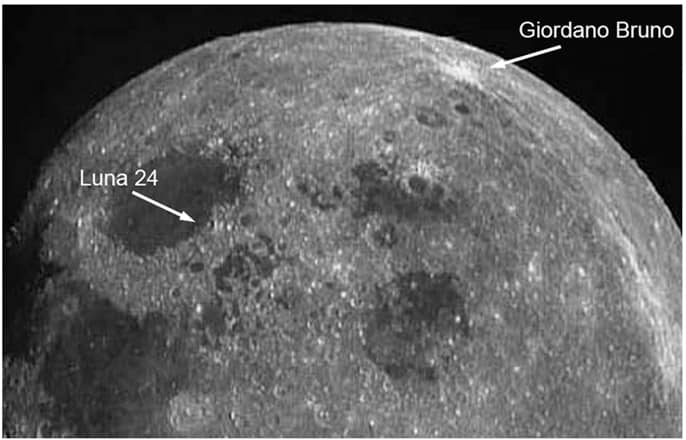

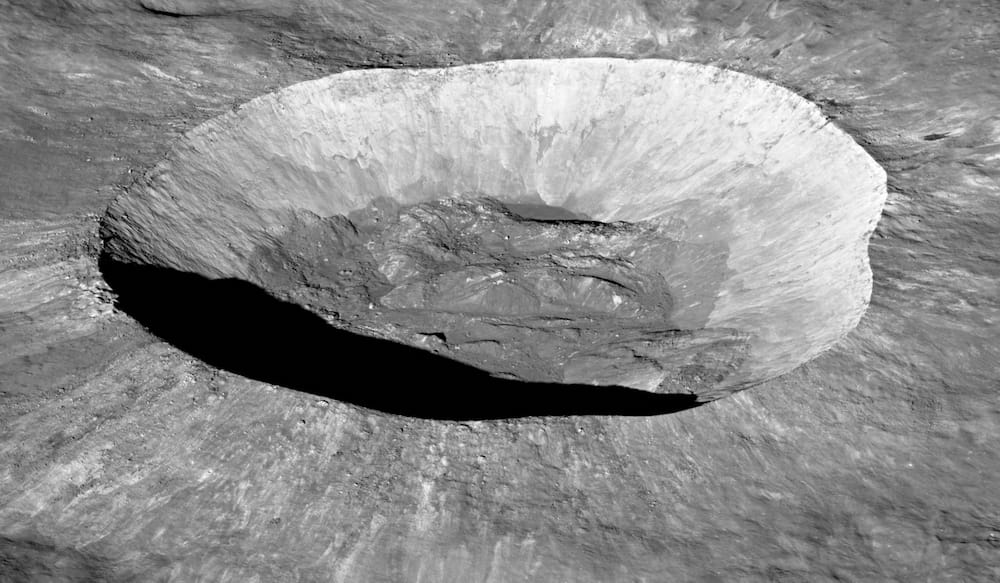

Over the years, historians and astronomers have put forward a number of theories about what phenomenon Gervase is describing. The most prominent theory, put forth by geologist Jack Hartung in 1976, proposes that the monks witnessed an asteroid or comet hitting the moon, causing a plume of molten matter to rise up from the Moon’s surface in a manner consistent with Gervase’s account. By narrowing down the physical location on the Moon from the description, Hartung believed that the monk’s could have been watching the formation of the Giordano Bruno crater, one of the youngest craters on the surface of the Moon.

This theory has been disputed, with one astronomer suggesting that the formation of such a crater would have created 10 billion kilograms of debris, causing at least a week of blizzard-like meteor storms on Earth. No accounts of such conditions have been found for this time period anywhere in the world.

Paul Withers, at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, believes the answer is much simpler:

I they happened to be at the right place at the right time to look up in the sky and see a meteor that was directly in front of the moon, coming straight towards them.

And it was a pretty spectacular meteor that burst into flames in the Earth’s atmosphere — fizzling, bubbling, and spluttering. If you were in the right one-to-two kilometre patch on Earth’s surface, you’d get the perfect geometry. That would explain why only five people are recorded to have seen it.

Imagine being in Canterbury on that June evening and seeing the moon convulse and spray hot, molten rock into space. The memories of it would live with you for the rest of your life.

Top image: The Moon of Canterbury Cathedral