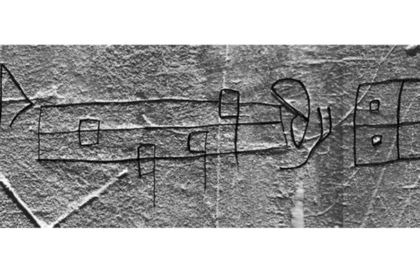

ABOVE: Arrival of Louis in England, from the ‘Chronica Majora’ of Matthew Paris, c.1236–59

When it comes to regnal lists and the royal family tree, there is always debate over whether Empress Matilda and Lady Jane Grey should be included as queens of England; Matilda controlled England briefly after she captured King Stephen, and Lady Jane was proclaimed queen by the late King Edward’s Privy Council. Though they were never crowned, it still seems unfair they are ignored, whilst the young Edward V is recognised as king despite also never being crowned. Matilda and Jane are usually not counted amongst the monarchs of England simply because they were not widely acknowledged in their own time; whilst their own inner circle of supporters proclaimed them queen, the vast majority of England and the nobility did not. Edward V, on the other hand, was widely recognised as king before the usurpation of Richard III.

There is another monarch, though, who is left off regnal lists even more frequently than Matilda or Jane, despite having far more success than either of them – King Louis I of England.

During the 1215 First Barons’ War, the nobility of England revolted against the despised King John. As John’s heir was still a child under the influence of his parents, the baron’s turned to France for a king. King Phillipe Auguste’s son, Dauphin Louis, was married to Blanche of Castile, granddaughter of John’s father, King Henry II of England. The nobility of England were desperate enough to offer the throne to Louis based upon that fairly tenuous claim.

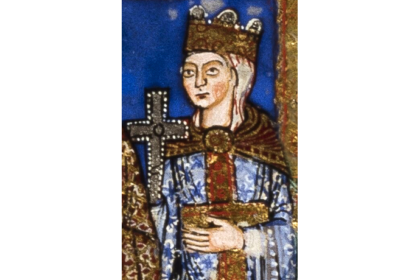

Louis and his army sailed to England on 21st May 1216, and John fled westward, avoiding a battle he knew he could not win. Louis met little resistance and quickly took all the territory en-route to London, and he was enthusiastically welcomed by the city on the 2nd June. He was proclaimed King Louis I of England at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral with much pomp and circumstance, and the nobles of England flocked to pay homage to him. Within a matter of months, and going largely unchallenged, Louis had control of at least half of England, and two-thirds of the barons of England were sworn to him.

Despite such rapid success, Louis’ fortunes changed when John died on the 19th October, 1216, leaving behind his 9 year old heir. John’s handful of remaining loyal supporters quickly secured the boy and had him crowned at Winchester Cathedral, and reissued the Magna Carter in the name of Henry III.

When news spread of John’s death, the barons previously loyal to Louis started to reconsider their position; a French prince was a good alternative to John, but to an innocent, malleable young boy? Louis quickly lost a lot of support.

Louis tried to maintain control of the country, but after the Battle of Lincoln on the 20th May, 1217, and the naval Battle of Sandwich on the 24th August, Louis agreed to the peace terms set forth by Henry’s councillors. The Treaty of Lambeth was signed in September, in which Louis agreed to give up all pretensions to the English throne in exchange for 10,000 marks.

Thus ended the brief rule of King Louis I of England.

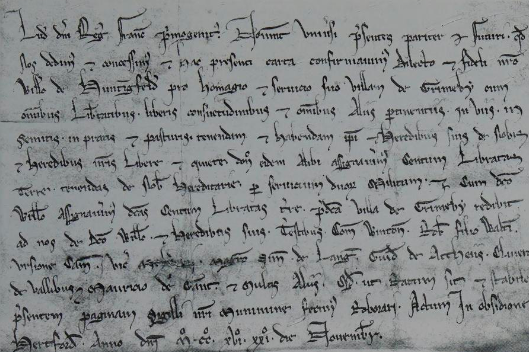

So why is Louis so completely ignored as a king of England? Louis was never crowned, but then again, nor was Edward V. And Louis certainly had far more control of the country than the young Edward ever did. Unlike Matilda and Jane, Louis was widely proclaimed. More than that, we can see that he was actively ruling England. He formed a council, and engaged in the business of the realm. At least one of his charters survives; it is regarding a seemingly minor matter, the grant of the manor of Grimsby to William of Huntingfield. Significantly, Louis does not claim the title of king of England in the charter. Nevertheless, he clearly regarded himself as having the authority to issue the grant. And he was widely proclaimed king and received homage as such from the majority of the nobility.

Stating that he is not considered a king of England because there was already a living king on the throne does not work for a similar reason; he was widely regarded as such, so why should we impose a different assessment? And it is important to remember that Louis was not claiming the throne by right of conquest, he was claiming a blood right via his wife, and was invited as such.

Perhaps part of the reason Louis is so often ignored by history is because he complicates the narrative of father-son inheritance. For such a short reign, and given that the throne quickly returned to the son and heir of the former king, it is easier to relegate him to the footnotes, rather than dedicating a chapter to him.

If you would like to read more about the life of King Louis I of England, who went on to be King Louis VIII of France, I highly recommend Catherine Hanley’s nonfiction book ‘Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England.’