Whilst Henry VIII is renowned for his complex marital life, his 13th century ancestress, Isabella of Angoulême, could give him a run for his money.

Isabella was the only child of the Count of Angoulême and the great-granddaughter of Louis VI of France, making her a great heiress and very desirable bride. Her birthdate is unknown, but it is likely that she was born in the early 1190s. In 1200, her father arranged the marriage between Isabella and the wealthy baron and landholder Hugh IX de Lusignan. Roger of Howden records that Isabella and Hugh had pledged themselves ‘verba de presenti,’ in other words, a full legal marriage, but Hugh chose to hold off on cohabitation due to Isabella’s extreme youth. Girls were considered as having reached full maturity by 12 years of age, so for Isabella’s youth to be given as a reason to delay their ‘espousement,’ she must have been at least a couple of years younger than this.

However, before Isabella could become Hugh’s wife in practice as well as in canon law, King John, worried about the power an alliance between Lusignan and Angoulême could hold, intervened with his own offer. John had recently had his first marriage annulled, and was in need of a wife. Some suggestions have been made that John was captivated by Isabella’s beauty, which was already renowned despite her youth, but I think it was more likely politics rather than lust which drove him to negotiate with Isabella’s father for her hand in marriage.

Given the haste of the volte-face, it is unlikely that the legal marriage between Isabella and Hugh was formally annulled. An annulment could have easily been sought on the grounds of non-consummation, but there is no evidence that this took place. Regardless of her legal status with Hugh, Isabella of Angoulême and King John were married on the 24th August, 1200. The Lusignans were, of course, furious at this underhanded mistreatment, but beyond rising up in rebellion, no further action was taken in the matter. That Isabella came into her vast inheritance of Angoulême upon her father’s death just 2 years later must have been a twist of the knife to the robbed Lusignans.

Fast forward to the year 1214. John and Isabella had 5 children together, including a daughter called Joan, born in 1210. Due to shifting politics, John was keen to ally with the Lusignans, and offered a betrothal between Joan and Hugh X, the son of Isabella’s former betrothed. Joan was sent to be brought up in the Lusignan’s household until she was old enough to be married, as was quite customary for the time.

Now, marrying your daughter to the son of your ex – who you may still technically be married to – is strange enough, but our story is not yet over. Because in 1216, King John died, leaving Isabella a very wealthy widow. In 1217, she left most of her young children in England and returned to her lands in France; her daughter, Joan, was also in France, still in the care of the Lusignans. In 1220, Isabella shocked the world when she announced that she had taken Hugh X Lusignan, her daughter’s betrothed, as her second husband!

Isabella wrote to her eldest son, now King Henry III, announcing the marriage and justifying it as being in Henry’s best interests. Arguably, the main reasons for writing was added by Isabella at the very end – to beg for her dower rights:

‘To her dearest son Henry, by the grace of God king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, count of Anjou, Y[sabel] by that same grace queen of England, lady of Ireland, duchess of Normandy, Aquitaine, countess of Anjou and of Angoulême, greetings and maternal blessings. We make known to you that when the counts of La Marche and Angoulême died, lord Hugh of Lusignan remained alone and without heir in the region of Poitou, and his friends did not permit our daughter to be married to him, because she is so young; but they counseled him to take a wife from whom he might quickly have heirs, and it was suggested that he take a wife in France. If he had done so, all your land in Poitou and Gascony and ours would have been lost. But we, seeing the great danger that might emerge from such a marriage — and your counsellors would give us no counsel in this — took said H[ugh], count of La Marche, as our lord; and God knows that we did this more for your advantage than for ours. Whence we ask you as a dear son that this please you, since it is of great utility to you and yours, and we diligently pray you to give him back his right, that is, Niort, Exeter and Rockingham, and 3500 marks which your father, once our husband, endowed us with: and so, if it please you, act towards him who is so powerful that he can not act towards you but to serve you well. For he has good will to serve you faithfully with all his power, and we are certain and take in hand that he will serve you well if you restore his rights to him: and therefore we advise that you take appropriate counsel on the aforesaid. And when it please you, send for our daughter, your sister, since we do not hold her; and by sure messenger and letters patent, fetch her from us.’

~

So, to summarise the complex web of marital relations, Isabella was married according to canon law to one man, but then married off to a second man, and a child she and the second man had together was betrothed to the son of the first man, who Isabella ended up marrying herself.

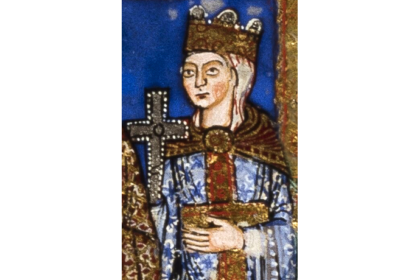

(Header Image: Isabella’s effigy in Fontevraud Abbey)