It is well known that in 1550, Mary almost went through with a plan to flee England into the welcoming, Catholic embrace of Charles V and her maternal, Spanish family. However, this wasn’t the first time that there were plans to rescue Mary from England; during 1535 and 1536, there was an ongoing dialogue between the Spanish ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, and Charles V about plans to smuggle Mary out of England.

Throughout this period, Mary was coming under increasing pressure to capitulate and conform to her father’s wishes, and particularly to take the Oath of Supremacy which proclaimed the illegitimacy of her parents’ marriage, and her own illegitimacy. Forced to reside in the household of her infant sister, Princess Elizabeth, Mary was kept out of sight and at times denied visitors. There are even reports of her being physically punished for her obstinacy. Rumours were flying round that either Henry was going to sentence Katherine and Mary to death, or that Anne was going to have them poisoned. To what degree these rumours were based in reality is hard to assess, but Chapuys certainly took them seriously; either way, Charles V was given reason to believe that his kinswomen were in danger.

The first mention I can find of any serious intention to rescue Mary from her ill-treatment is in a letter from Charles V to Chapuys written on the 5th January, 1536, in relation to the possibility of a match between Mary and the King of Scotland, James V. Charles’ vision was to rescue Mary and marry her to some eligible Catholic king, prince, or royal duke. The duke of Angouleme and a Portuguese match were also possibilities mentioned across the letters between Charles and Chapuys. There was little consideration for Katherine; as a good Christian wife, she could not, and would stoutly refuse to, abandon her husband or her position as queen – up until her death she clung to the hope that she would be restored to her former status as wife and queen to King Henry VIII. But until then, as heir to the throne and hope for a Catholic England, Mary must be safeguarded.

~

5th JANUARY 1535 CHARLES V to CHAPUYS

…A few days ago there returned to us maitre Godscalke, whom, as you know, we had sent to the king of Scots. By his report, and by the written answer he has brought from the said King, we find that he would be very glad to have in marriage our said cousin of England; but, thinking it impossible that she should be delivered to him, he desires us to suggest someone else of our blood for him to marry. On which subject we make him such answer as you will see by the copy which we send with this; so that, in conformity therewith, you will consider if there be any means of getting away (retirer) the said Princess; on which subject you will inform us on the first opportunity, as well as what has happened in Ireland since your letters, and if the news reported of the earl of Kildare are confirmed.

~

In early February 1535 Chapuys seems to have posed the suggestion of leaving England as a hypothetical to ‘the Princess’ as he always called her, though she had been stripped of the title some 18 months prior, to which Mary had responded favourably. Shortly thereafter, whether merely due to his suspicious nature, or due to information received from Cromwell’s informants, Henry seems to have become aware of the plans, stating that he would not allow Mary to join her mother’s household for fear that ‘the Princess were taken out of this kingdom, or if she herself escaped, as she might easily do by night if she were with the Queen her mother: for he perceived some indication that your Majesty would be glad to withdraw the said Princess somehow.’

~

9th FEBRUARY 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…As to the possibility of withdrawing the Princess from hence, the thing is so hazardous at present that I doubt if she would listen to it. For, besides that one must put oneself at the mercy of the wind, she is so strictly guarded that I can scarcely communicate to her anything; for, apart from her indisposition, I have only suggested to her whether she would not like to be beyond the sea; and she replied that she desired nothing else…

25th FEBRUARY 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…The King heard me patiently and graciously. and, instead of answering as usual that he knew better than anyone else how to provide for his daughter, he very gently answered he wished to do his utmost to procure his daughter’s health, and would proceed with the same diligence about it as he had begun, and that, since the Queen’s physician could not assist, he would find others. But. on the other hand, while seeing to the health of his daughter, he must not forget what was due to his own honor, which would be injured if, by bad keeping, the Princess were taken out of this kingdom, or if she herself escaped, as she might easily do by night if she were with the Queen her mother: for he perceived some indication that your Majesty would be glad to withdraw the said Princess somehow, and that I knew well what had been put forward touching the marriage of his said daughter between your Majesty and the king of France, which put him all the more in doubt, and made him consider how to prevent this. I remarked that there was no probability that your Majesty would attempt to steal away the said Princess, for several reasons that I alleged, and that, during the five years these matters had lasted, there had not been the slightest indication of it. He then said there was no great occasion to put the Princess again in the Queen’s hands, for it was she who had put it into her head to show such obstinacy and disobedience, as all the world knew; and although sons and daughters were bound to some obedience towards their mothers, their chief duty was to their fathers, and since the Princess could not have much help of the Queen, and it was clear the whole matter proceeded from the latter, she must submit to his pleasure. I did not wish to dispute with him on the subject…

…Whatever pretence the King makes about the Princess’s illness, he has been very cold; in fact, she was taken ill on Friday, and he did not send his physician thither till Thursday after, and I do not know if he would have gone even then if I had not for three days importuned Cromwell… As to getting her away from here, if the King do not remove her from hence, it could be accomplished by having a pinnace on the river and two armed ships at the mouth of the river; at least I could find means to get her out of the house almost at any hour of the night…

~

Chapuys made discreet enquiries about how this plan could be arranged, consulting with sympathetic lords, and feeling out the lay of the land; how could Mary be secretly smuggled away from guardians and out to sea without detections?

~

4th MARCH 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…As to getting the Princess away from here, it would not be difficult if she dwelt at the Tower, provided the equipage were supplied of which I lately wrote, viz.:—”Ung vasseaul de remmer que fut assez suffisant a ung besoing de son secource des petites barges qui pour les autres navires estans en lentrée de la riviere conuiendroit estre bien armée pour soubstenir limpetu des grans bouz quen pourroyt la venir.” (google transl. A remnant vessel that was sufficient enough to meet the need for his help from the small barges which, for the other ships at the entrance to the river, should be well armed to support the large boats that could come there.) If the wind be not favorable for her departure there would be no fear of the great ships here, because she could leave by the same wind as others did. But as it is proposed to change her lodging, we must wait to know where her residence will be fixed, and devise other expedients accordingly. As to the assurance of the persons of the Queen and Princess, I think the first thing that these lords would attempt to do would be that (a change of her lodging ?). I have not yet been able to talk with anyone, but hope, in three or four days, to communicate with those of whom I have written, or with some other person of the same will and importance, proposing the matter as of myself. For greater assurance I have frequently urged upon Cromwell and others of the Council that they ought to show great consideration for those two I dies who, even if there were mortal war with your Majesty, might be the means of pacification, like the mother of Coriolanus. This he has often confessed to be true: and I trust that if any outbreak took place, the King would not be too hasty to use violence to those ladies. Pending the issue of affairs he would probably seize them and put the Princess in the Tower, and, if so. I imagine the Queen and Princess would not be so much at his command as he supposes, as the Captain seems to be a good servant of your Majesty and the said ladies…

7th MARCH 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…The other day there dined with me the son of lord Darcy, and the brother of the earl of Ublchez, with two other gentlemen of the Court, when we appointed to go and see the said lord Darcy yesterday. I could have wished the appointment had held, so that I might have talked with him without suspicion, but the meeting has been prevented. And as I could not go I sent one of my men to ascertain what means could be taken for the security of the Queen and Princess in case of disturbance. He notified to me that he must have time to give a precise answer, though he had no doubt that means could be found to withdraw them; besides that he considered that even if they remained in the King’s hands they would be in less danger than now; for the King would be in such perplexity that he would have to think well before ill-treating them. The good Lord hastens always this redemption (haste tousjours ceste redemption), and would like to be warned of the time, in order to withdraw into his country, where he has a castle near the sea. I am sure that if the ladies fall into the keeping of him of whom I wrote lately, they would be out of danger; for he desires their good no less than they themselves, and is anxious for an opportunity to show his good-will…

~

In late March or early April, the stars seemed to align, when a number of Spanish ships were docked in the Thames, which could spirit Mary away. It was at this point that Chapuys informed Mary of the plot, to which she responded by ‘saying she desired nothing else.’ The plan fell through, as Mary was unexpectedly moved from her convenient location at Greenwich, and the lack of time to get Charles’ approval to proceed.

~

5th APRIL 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…Since the little bastard removed from Greenwich, considering that one of the galleons of La Renterie was on the other side of the river, and that there were some other Spanish ships here, by means of which the Princess might be saved, I sent to her to know if she would agree to it. She gave ready ear to the suggestion, saying she desired nothing else, and has since sent two or three times for my man to solicit the matter; but her sudden departure broke off the enterprise, to which also I did not dare commit myself, not having commandment from your Majesty, considering the practises put in train, since it pleased you to charge me to write what means there might be of withdrawing her. Nevertheless the said Princess continues in her purpose to go away, and has sent to desire me by my servant, who has just come from seeing her, that, for the love of God, I will contrive to remove her from the danger which is otherwise inevitable; adding, where she is now there is no means of saving her by night, and that as soon as it was fine weather she would go out walking to see what arrangement could be made to come upon her by surprise in the daytime, and so that it should appear as little as possible that it was by her consent, for the sake of her own honour, and the less to irritate, the King her father. The house where she lies is 12 miles from this river, and if once she could be found alone it would be easier to save her than it was at Greenwich, for we could put her on board beyond Gravesend, past the danger of this river. The matter is hazardous, and your Majesty will take it into due consideration. London, 5 April 1535.

~

Charles V wrote to Chapuys encouraging him to find a discreet method of smuggling Mary out of England; but though Chapuys reported that Mary was desperate to escape the country, he despaired of finding the means to proceed with it.

~

17th APRIL 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…Ill as the Princess is, she does not cease to think if there be any means of escaping; and on this subject she had a long conversation with one of my men, begging me most urgently to think over the matter, otherwise she considered herself lost, knowing that they wanted only to kill her. She has not had leisure to visit the neighbourhood of the house where she is, nor to devise means how she could get away night or day. And because I see the thing is difficult I keep her in hope of a speedy remedy by some other means, and endeavour to remove her suspicion that foul play is intended against her…

LATE APRIL 1535 CHARLES V to CHAPUYS – SUMMARY

Chapuys will do well to take heed of every method of getting the Princess out of England, not doubting that it will be done with secrecy and discretion.

5th MAY 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…As to what is contained in your last letters about getting away the Princess, my man returned from her this morning, and has reported that she thinks of nothing else than how it may be done, her desire for it increasing every day, especially since the said monks have been executed; for, since then, her gouvernante has been continually telling her to take warning by their fate. Till now she has not been able to see how it could be done; nor I either, as the place is unknown to me. Whatever can be devised I will notify to your Majesty…

~

By the middle of the year, as the tensions between Mary and her father escalated, Chapuys reported that he was prevented from sending his people to Mary, and communication with her became difficult. The last reference to the plan in 1535 was in September, when Chapuys wrote with a heavy heart that ‘I have laboured long for this end, but to no purpose.’

~

5th JUNE 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…As to what your Majesty wrote to me about gaining time with the English, and keeping up practises skilfully during the assembly at Calais and the voyage of your Majesty, I will take all possible pains; likewise to reply in conformity with your Majesty’s letters, if I am asked about the disturbances in Ireland, without forgetting to inquire about means of carrying away the Princess. She and the Queen, her mother, have been much consoled by hearing of the prosperity of your Majesty, and of the thought you have given to their affairs, for which they do not cease to pray God for your welfare…

3rd AUGUST 1535 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

…I have not yet wished to go to the chase, nor do I know that leave would be given me to visit the Princess, seeing that the chase is round about her, and that I am not allowed to send my men to her…

13th SEPTEMBER 1535 CHAPUYS V

…The Princess has been visited by the King’s and Queen’s physicians, and, thank God, is well for the present; but the said physicians doubt that this winter she may relapse into a worse condition than ever; and, as she detests all medicines, they see no other remedy except that she should be placed somewhere where she can have recreation, as she would with the Queen her mother, or elsewhere, without being in the servitude and captivity in which they are. I have laboured long for this end, but to no purpose. London, 13 Sept. 1535.

~

Less than 4 months later, Mary’s mother, Katherine of Aragon, was dead. Most historians say that with Katherine’s death, Charles lost any interest in helping Mary, preferring to smooth over his relationship with Henry. In fact, the letters between Chapuys and Charles show a new urgency in rescuing and safeguarding Mary, possibly due to fears that now that Katherine was out of the way, that Mary would be seen as unprotected. Chapuys outlined a detailed plan involving drugging Mary’s Boleyn-appointed attendants and smuggling her onto a ship at Gravesend. At the time of writing the letter, in February 1536, just over 12 months had passed since the first possibility of rescuing Mary had been raised.

~

29th JANUARY 1536 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

Wrote at length on the 21st. My man has since arrived, by whom I have learnt part of what has been proposed by the Regent of Flanders and also by De Roeulx touching the enterprise, the transport of which is the question. The rest I am to learn from the man whom De Roeulx will send hither shortly. To say the truth, I fear that the time for the enterprise has gone by, at least for a while, seeing that, [the Princess] is to be removed in six days from the place where everything was prepared, and would have been removed already, but for the arrangements for the Queen’s burial, to a place very unsuitable for the attempt. For this reason I had asked the house to which she is to be removed for the Queen, and though I have no hope of success, I will do my best to discover some means of carrying it into effect. This very morning I secretly sent for one of those who had hitherto been of counsel in the matter, but it has become more difficult because my men are forbidden to frequent the neighbourhood. If matters could be delayed, I think a better opportunity would offer, because the removal of the personages cannot but be to a more propitious place…

10th FEBRUARY 1536 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

Sire, — Yesterday arrived the personage sent by M. de Roeulx to examine the plans for the enterprise, and to instruct me in the order to be taken. I fear, for the reasons which I stated in my last letter to your Majesty, the opportunity is gone. I have not, however, as yet received the answer of the person whom the affair concerns, and as that answer shall be, we will act to the best of our ability. Your Majesty shall have notice in time…

17th FEBRUARY 1536 CHAPUYS TO CHARLES V

Sire, — In my letter of the 10th I informed your Majesty of the arrival of the person despatched by M.de Roeulx, and I forthwith sent notice to the Princess by her confidential servant. The servant returned yesterday with an answer, that I need not keep her informed in detail of the plans for carrying her off ; she left the whole arrangement to my discretion, having entire confidence in me, and I was to settle everything ; she herself would he in readiness to leave the house, and this she thought she could do if we would provide her with a sleeping draught for the women who were placed about her ; she would have to pass the window of her governess ; but once outside the house she could find means to unlock or break open the door of the garden.

Sire, her anxiety to escape from her present unhappy situation is so great that I think if I told her to go to sea in a sieve she would do it, and this makes me fear that her eagerness blinds her to the difficulties of the enterprise. When the experiment is tried, those difficulties will be found more considerable than she anticipates, and she has no person of experience to advise her. If the house in which they have placed her be really so easy to leave, they may have purposely laid the temptation in her way, that they may have an excuse for treating her more harshly. She believes that there is no guard ; but a guard there may be, notwithstanding, without her knowledge, as there was last year at Greenwich.

Sire, her present residence is for many reasons less convenient than the house where she was before. It is fifteen miles further from Gravesend, and at Gravesend M. de Roeulx says that she must embark, the mariners not caring to venture further up the river. She would have forty miles to ride, which she could not accomplish without relays of horses, and do what we would, I think she could not escape being detected and overtaken. The town adjoining is full of men and horses, and there are towns and villages along the road where she might easily be discovered and stopped.

Doubtless, could she be brought below Gravesend as the captain desires, the rest would then be easy ; but the difficulty is the distance she must ride. If she embark near London, there will be danger on the passage down before she can be brought clear of the river. The captain says, among other excuses, that the scrutiny is so close that he cannot venture to bring any men with him below deck. There is no real obstacle here, however ; the men might be dispersed in other vessels and landed at Gravesend, where they could rejoin him. The Princess thinks, and I learn the same thing elsewhere, that about Easter she will be removed again, perhaps to the old house, or it may be even nearer.

Nevertheless, Sire, ardently as the Princess longs to escape from her trouble, she would deem it far better and far safer that something should be undertaken of a larger kind, and a general remedy be devised for the service of God, for the salvation of the unnumbered souls which are now going the way to perdition, and for the repose and tranquillity of Christendom;

Supposing her carried off, which will not be without difficulty and hazard, the question will not be settled. She says herself that stronger measures may be required, and the victory perhaps, after all, might then be less easy to achieve. The King is now off his guard ; the realm is undefended, and he scarcely thinks of making preparations. Her escape might drive him to despair, and with the help of his money he might do many things.

For my own part, I think if the Princess were once in your Majesty’s hands, the King would drop his bravado, and would not kick against the pricks. The Princess at any rate never ceases to entreat me to implore your Majesty to take up the matter promptly and swiftly; events move too slowly for her; and when the time comes she is prepared for death. She

wishes me to despatch a messenger expressly to solicit your Majesty ; in fact, she would have had the late Queen’s physician go, were he willing to leave England. But I urged that

in doing so she would show some distrust of your Majesty’s good will ; I assured her that the opportunity was watched for with the utmost vigilance, and I satisfied her that I ought not to send. I persuaded the physician to stay where he was, by telling him that the Princess might require his help, and could trust no one but himself. The King sent him to attend upon her. I spoke myself about it after the Queen’s death ; and the King gave permission that he should have access to her apartments at all times and seasons.

Report says, Sire, that a number of the old servants of the Queen her mother are to be transferred to the Princess’s household, especially the head groom of the chamber, who is to hold the same office. Should this turn out true, there will be far less difficulty in carrying her off ; the groom of the chamber being a man of ability — as fit a person for such a business as could be found anywhere. If only she return to her old house at Easter, so much the better, also. The time will be more convenient. The King at that season is usually at a distance, and the sea will be less dangerous.

Should it be determined finally to make the attempt, it will not be for your Majesty’s honour that I should remain here ; for all the world will not be able to persuade the King that I was not the contriver and promoter of the business, and things might, perhaps, go hard with me. He has a large opinion of his own greatness, and he would like to show that he neither fears nor regards man ; his concubine hates me because I have always told him the truth, and opposed his accursed obstinacy ; and, as soon as the preparations are complete, I had better hasten off, with two or three of my people, to make a tour in Flanders. As I am known to have communicated with M. de Roeulx’s servant, it is next to impossible that he should not discover my hand ; if he find me out, he will certainly destroy me ; while my going away may, perhaps, divert their attention.

Your Majesty will let me know your pleasure, and I will forthwith obey you. I will only beseech your Majesty not to impute what I have written to a want of will or courage. I am ever ready to die in your Majesty’s service.

~

Chapuys himself plainly states why the plan was not put into action; her location at that was too far from the rendezvous site at Gravesend. Both Mary and Chapuys had been given to believe that she would be at a more accessible location by Easter, during which time everyone’s guard would be down due to the festivities. Whilst Charles asked Chapuys to go forward with the plans as quickly and discreetly as possible, he dissembled to Henry, offering a new hand of friendship in the wake of Katherine’s death, Mary likewise pretending to withdraw her defiant claims to the status of legitimate Princess by feigning an interest in entering the religious life.

~

29th FEBRUARY 1536 CHARLES V to CHAPUYS – SUMMARY

His last letters received were of the 18th and 30 Dec., and of the 9th ult., touching the sickness and death of the queen of England. Laments her decease, and the desolation of the Princess, her daughter. Desires to hear of the Princess’ treatment—whether she continues at the same place as when her mother was alive—and whether there is any means of getting her away (de la transpourter ailleurs), or making some change in her estate….

Since the above was written, received on the 25th his letters of the 21st and 29th Jan. Approves of his conduct in consoling and advising the Princess…Agrees with his advice that the Princess should feign a wish to enter religion. Delays writing to her lest his letters be intercepted; but Chapuys may assure her that he hopes to remedy her treatment (son affaire) to her satisfaction, whatever turn matters take, either for peace or war

~

There is no further mention of the scheme in the letters. In 1536, Easter fell on the 16th April. By this time there were increasingly loud whispers about a breakdown in the royal marriage. Far better for Mary to stay where she was and see to how things played out. If Anne Boleyn was cast aside, as Mary’s own mother had been, Mary would be in a strong position as the eldest child of King Henry, regardless of her legal status.

Of course, looking back, we know that Anne was arrested just two weeks after Easter, and executed on the 19th May. This wasn’t the end of Mary’s troubles; Henry was determined that his daughter would capitulate and acknowledge her illegitimacy and himself as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. In the end, Mary did comply, and she was restored to her father’s favour and her position at Court. For the rest of Henry’s reign, Mary was able to more or less retain Henry’s favour; it wasn’t until Edward’s ascension and further reforms to the Church that she would once again face the dangers of royal wrath; and likewise, would once again plan to flee.

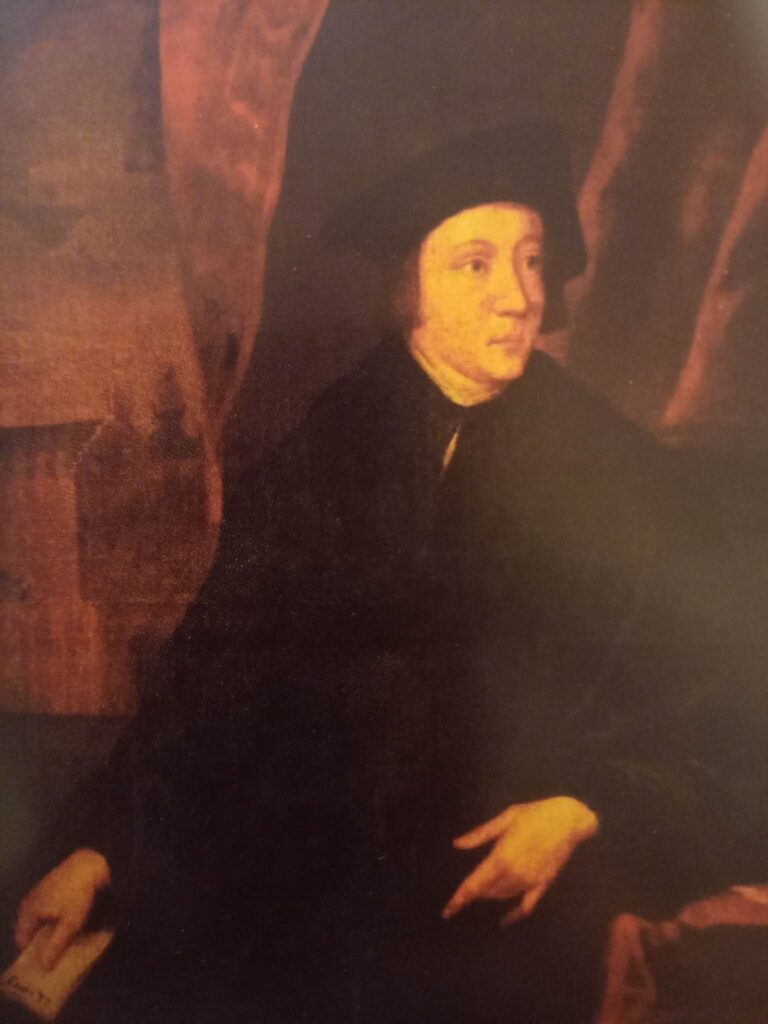

Top image: Portrait miniature of Mary by Lucas Horenbout, c.1525.

[…] MARY’S PLANNED FLIGHT FROM ENGLAND […]