Celebrating the new year is a tradition which has a long history. One of the most evocative medieval accounts is in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.’ This 14th century chivalric romance was written in Middle English, and is part of the medieval Arthurian tradition. The author of the text is unknown, however due to a number of similarities in form, diction, and dialect, it is believed that the author wrote a number of poems, and has been dubbed the ‘Pearl Poet,’ after another one of their works. In fact, so little is known about the origins of the text, that we don’t know what it was original called; the title of ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ was given centuries later.

The New Year’s festivities described in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ are an idealised version of courtly life – how lavish and extravagant the celebrations must be in idyllic Camelot. Sadly, as we don’t have a precise date for the text, we cannot say if it was supposed to be a direct of model of a particular English king’s court and festivities.

Below, I have first provided a modern translation of the text, and then afterward the original Middle English text.

~

MODERN TRANSLATION BY PAUL DEANE

While the year was as young as New Years can be

the dais was prepared for a double feast.

The king and his company came in together

when mass had been chanted; and the chapel emptied

as clergy and commons alike cried out,

“Noel! Noel!” again and again.

And the lords ran around loaded with parcels,

palms extended to pass out presents,

or crowded together comparing gifts.

The ladies laughed when they lost at a game

(that the winner was willing, you may well believe!)

Round they milled in a merry mob till the meal was ready,

washed themselves well, and walked to their places

(the best for the best on seats raised above.)

Then Guinevere moved gaily among them,

took her place on the dais, which was dearly adorned

with sides of fine silk and a canopied ceiling

of sheer stuff: and behind her shimmering tapestries from far Tarsus,

embroidered, bedecked with bright gems

that the jewelers would pay a pretty price for

any day,

but the finest gem in the field of sight

looked back: her eyes were grey.

That a lovelier’s lived to delight

the gaze – is a lie, I’d say!

But Arthur would not eat till all were served.

He bubbled to the brim with boyish spirits:

liked his life light, and loathed the thought

of lazing for long or sitting still longer.

So his young blood boiled and his brain ran wild,

and in many ways moved him still more

as a point of honor never to eat

on a high holiday till he should have heard

a strange story of stirring adventures,

of mighty marvels to make the mind wonder,

of princes, prowess, or perilous deeds.

Or someone might come, seeking a knight

to join him in jousting, enjoying the risk

of laying their lives on the line like men

leaving to fortune the choice of her favor.

This was the king’s custom at court,

the practice he followed at pleasant feasts held

in his hall;

therefore with bold face

he stood there straight and tall.

As New Years proceeded apace

he meant to have mirth with them all.

So he stood there stock-still, a king standing tall,

talking of courtly trifles before the high table.

By Guinevere sat Gawain the Good,

and Agravaine of the Heavy Hand on the other side:

knights of great worth, and nephews to the king.

Baldwin, the bishop, was above, by the head,

with Ywain, Urien’s son, sitting across.

These sat at the dais and were served with due honor;

and many mighty men were seated on either side.

Then the first course came with a clamor of trumpets

whose banners billowed bright to the eye,

while kettledrums rolled and the cry of the pipes

wakened a wild, warbling music

whose touch made the heart tremble and skip.

Delicious dishes were rushed in, fine delicacies

fresh and plentiful, piled so high on so many platters

they had problems finding places to set down

their silver bowls of steaming soup: no spot

was clear.

Each lord dug in with pleasure,

and grabbed at what lay near:

twelve platters piled past measure,

bright wine, and foaming beer.

~~~

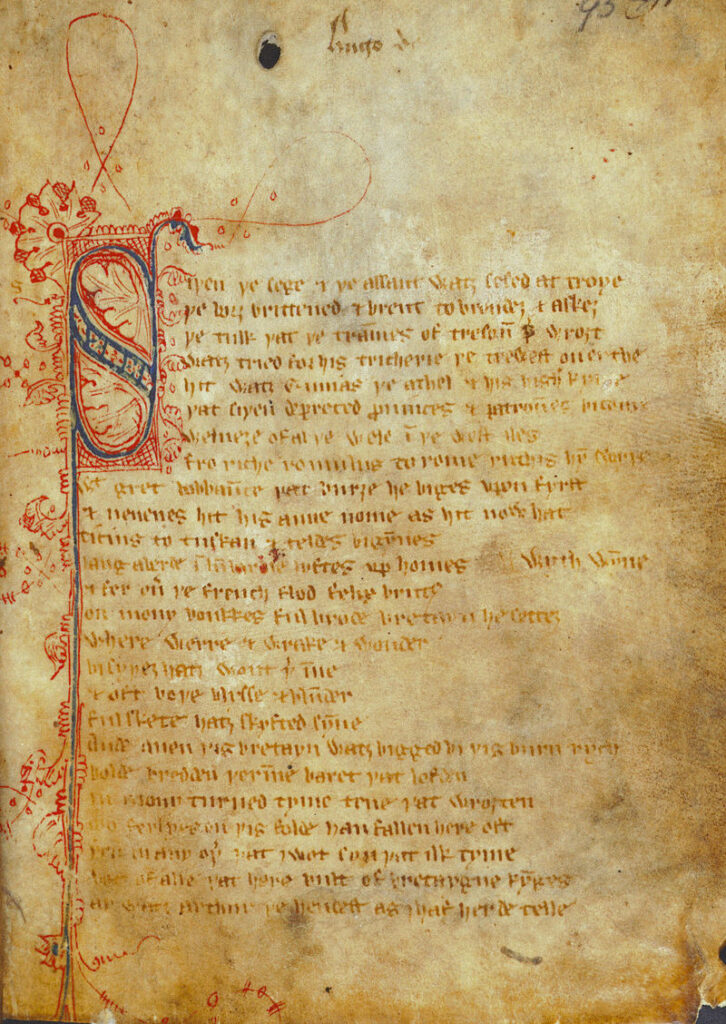

ORIGINAL TEXT

Wyle Nw Ȝer watz so ȝep þat hit watz nwe cummen,

Þat day doubble on þe dece watz þe douth serued.

Fro þe kyng watz cummen with knyȝtes into þe halle, Page 3

Þe chauntré of þe chapel cheued to an ende,

Loude crye watz þer kest of clerkez and oþer, [folio 92r]

Nowel nayted onewe, neuened ful ofte;

And syþen riche forth runnen to reche hondeselle,

Ȝeȝed ȝeres-ȝiftes on hiȝ, ȝelde hem bi hond,

Debated busyly aboute þo giftes;

Ladies laȝed ful loude, þoȝ þay lost haden,

And he þat wan watz not wrothe, þat may ȝe wel trawe.

Alle þis mirþe þay maden to þe mete tyme;

When þay had waschen worþyly þay wenten to sete,

Þe best burne ay abof, as hit best semed,

Whene Guenore, ful gay, grayþed in þe myddes,

Dressed on þe dere des, dubbed al aboute,

Smal sendal bisides, a selure hir ouer

Of tryed tolouse, and tars tapites innoghe,

Þat were enbrawded and beten wyth þe best gemmes

Þat myȝt be preued of prys wyth penyes to bye,

in daye.

Þe comlokest to discrye

Þer glent with yȝen gray,

A semloker þat euer he syȝe

Soth moȝt no mon say.

Bot Arthure wolde not ete til al were serued,

He watz so joly of his joyfnes, and sumquat childgered:

His lif liked hym lyȝt, he louied þe lasse

Auþer to longe lye or to longe sitte,

So bisied him his ȝonge blod and his brayn wylde.

And also an oþer maner meued him eke

Þat he þurȝ nobelay had nomen, he wolde neuer ete

Vpon such a dere day er hym deuised were

Of sum auenturus þyng an vncouþe tale,

Of sum mayn meruayle, þat he myȝt trawe,

Of alderes, of armes, of oþer auenturus,

Oþer sum segg hym bisoȝt of sum siker knyȝt

To joyne wyth hym in iustyng, in jopardé to lay,

Lede, lif for lyf, leue vchon oþer, Page 4

As fortune wolde fulsun hom, þe fayrer to haue.

Þis watz þe kynges countenaunce where he in court were,

At vch farand fest among his fre meny [folio 92v]

in halle.

Þerfore of face so fere

He stiȝtlez stif in stalle,

Ful ȝep in þat Nw Ȝere

Much mirthe he mas withalle.

Thus þer stondes in stale þe stif kyng hisseluen,

Talkkande bifore þe hyȝe table of trifles ful hende.

There gode Gawan watz grayþed Gwenore bisyde,

And Agrauayn a la dure mayn on þat oþer syde sittes,

Boþe þe kynges sistersunes and ful siker kniȝtes;

Bischop Bawdewyn abof biginez þe table,

And Ywan, Vryn son, ette with hymseluen.

Þise were diȝt on þe des and derworþly serued,

And siþen mony siker segge at þe sidbordez.

Þen þe first cors come with crakkyng of trumpes,

Wyth mony baner ful bryȝt þat þerbi henged;

Nwe nakryn noyse with þe noble pipes,

Wylde werbles and wyȝt wakned lote,

Þat mony hert ful hiȝe hef at her towches.

Dayntés dryuen þerwyth of ful dere metes,

Foysoun of þe fresche, and on so fele disches

Þat pine to fynde þe place þe peple biforne

For to sette þe sylueren þat sere sewes halden

on clothe.

Iche lede as he loued hymselue

Þer laght withouten loþe;

Ay two had disches twelue,

Good ber and bryȝt wyn boþe.

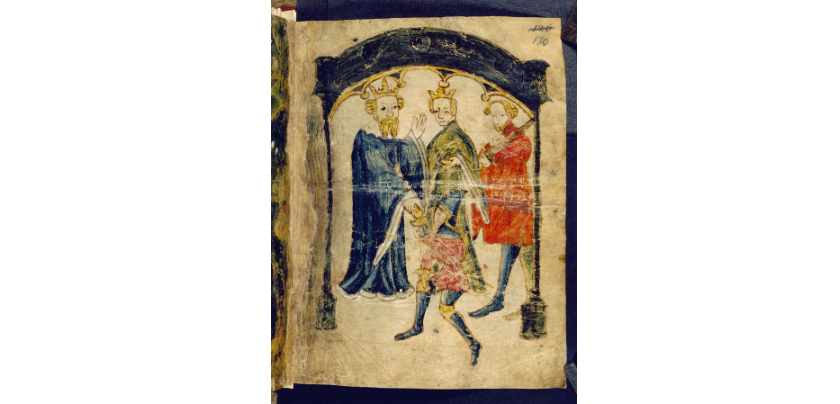

(Header Image: Illustration from the original manuscript of ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’)