Catherine Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII, is reputed as the first authoress to publish under her own name. However, this is a considerable simplification of a much broader topic of the women writers in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period.

In 1545, ‘Prayers and Meditations’ was ‘collected out of holy workes, by the most vertuous and gracious Princesse Katherine queene of England, Fraunce and Ireland.’ This wasn’t Parr’s first work; the previous year she had anonymously published ‘Psalms or Prayers.’

Prior to Catherine Parr’s renowned publication, it was acceptable to identify that a woman had written, translated, or compiled a text; it is just that their actual name did not appear in print. An example of this took place just two decades earlier. In 1524, Margaret Roper, the daughter of Thomas More, anonymously published a translation of Desiderius Erasmus’ ‘Precatio Dominica’ as ‘A Devout Treatise upon the Paternoster.’ However, Jaime Goodrich, a historian of Early Modern women writers argues that though the authoress was only identified as ‘a yong vertuous and well lerned gentylwoman of xix yere of age,’ amongst the learned circles who would read such a text, it was well known that Margaret was the woman behind the publication.

A letter Thomas More wrote to Margaret’s tutor offers an insight into one reason women should not publish their works, or at least should not be so vain as to claim credit for it: ‘Since erudition in women is a new thing and a reproach to the sloth of men, many will gladly assail it.’ Thomas More was famous for promoting the education of women, but many still clung to the old idea that an educated woman was a dangerous thing, and could lead to the breakdown of society. He feared that if people (read: men) saw women being vain about their achievements, it would be used as a weapon against the cause.

But if we rewind further, we can see that at least one authoress was identified in her complete English manuscript in the Middle Ages.

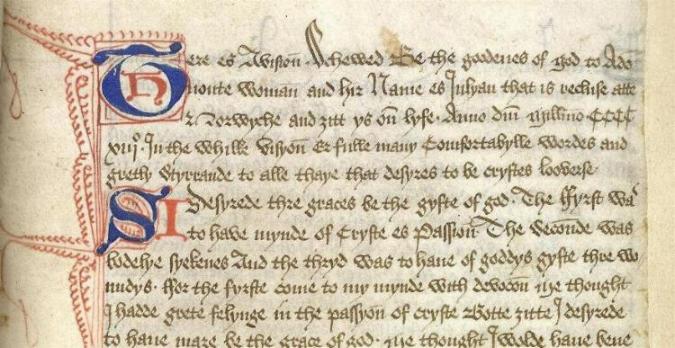

Written in Middle English, ‘Revelations of Divine Love’ was composed by Julian of Norwich in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Julian was an anchoress in Norwich who experienced mystic visions during a near-fatal illness, and wrote about them in a book. This is the first book in English known to have been written by a woman. Julian wrote two versions of ‘Revelations of Divine Love,’ known as the ‘Short Text’ and the ‘Long Text.’ The ‘Short Text’ seems to have been written soon after she recovered from the illness which induced her visions in May 1373, and were then later expanded upon in the ‘Long Text.’

In the book, Julian avoids identifying herself, referring to herself as ‘a simple creature unlettered.’ Being illiterate, she relied on scribes to write for her, as many did during this period. The scribe who wrote the single surviving manuscript of the finished text with the line:

‘Here es a vision schewed be the goodenes of god to a devoute woman and hir name es Julyan that is recluse atte Norwyche and zitt ys on lyfe anno domini millesimo ccccxiii’

(Here is a vision shown by the goodness of God to a devout woman, and her name is Julian, who is a recluse at Norwich and still alive, A.D. 1413.)

From the phrasing, it has generally been agreed that this was the scribe’s own addition, rather than Julian’s own words. Nevertheless, the manuscript has a clear female author identified.

So why isn’t Julian of Norwich considered the first published English authoress? Well, to put it simply, it is because the printing press had yet to be invented.

When we talk about publishing, we are referring specifically to works which have been through the printing press. William Caxton wouldn’t bring the printing press to England until 1476, more than a century after Julian is first believed to have started work on her manuscript.

‘Revelations of Divine Love’ was written during a time in which new manuscript copies were created by handwriting text onto new parchment folios. Around 1450, this did happen; one James Grenehalgh included the ‘Short Text’ in an anthology of religious texts compiled for Syon Abbey. But otherwise, Julian’s book is not believed to have been widely disseminated in her lifetime; it is unclear how many original copies were made, or if more than a small handful of people read it.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1670 when a Benedictine monk called Serenus de Cressy had Julian’s book published for a convent on English nuns in Cambrai, under the name ‘XVI Revelations of Divine Love, shewed to a devout servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third.’ This is considered the first official publication of Julian of Norwich’s book. How de Cressy came upon the book is unclear; it certainly would not have been allowed during the English Reformation or the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Nevertheless, it is disingenuous to ignore the fact that Julian’s book was copied and made available as early as the 15th century, and with her name clearly labelling her as the authoress. Whilst the printing press did revolutionise the creation and dissemination of texts, it should not act to erase the literary achievements of women prior to its arrival in England

This should not undermine the significance of Catherine Parr’s publication; however, we should remember that women had been writing in English and disseminating their works for at least several centuries before this. Here I have presented just a small sample of a much larger area of research. Because Julian of Norwich’s ‘Revelations of Divine Love’ is the earliest text so far that was attributed to a woman. I’m sure in the future many more will come to light.

Top image: Portrait of Catherine Parr by an unknown artist, c.1544-45