Stonehenge is one of England’s most iconic attractions. The prehistoric monument is believed to have been constructed from 3000 to 2000 BCE. There are many theories about the purpose of Stonehenge, and there is almost constant research into its mysteries. The research and evidence about Stonehenge and its origins are far too vast for me to address here, and in any case, falls outside of our timeline.

However, what I am going to look at are accounts and depictions of Stonehenge in the medieval and Tudor periods. Though it doesn’t seem to have attracted the same level of interest then as it does now, Stonehenge does appear scattered throughout the sources, sometimes just as little marginal sketches, easily overlooked. I cannot say that this is a complete collection of sources, but it does bring together most of the accounts I have come across in my research.

~

Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum, c.1135

translated by Diana E. Greenway

‘There are four wonders which may be seen in England […] The second is at Stonehenge, where stones of remarkable size are raised up like gates, in such a way that gates seem to be placed on top of gates. And no one can work out how the stones were so skilfully lifted up to such a height or why they were erected there.’

~

Xxtracts from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, c.1136

translated by Michael A. Faletra

‘As Aurelius looked upon the place where the dead lay buried, he was moved to great pity and burst out in tears. For a long time he considered many different ideas about how to memorialise this site, for he felt that some kind of monument should grace the soil that covered so many noblemen who had died for their homeland […] Merlin said to him: “If you wish to honour the grave of the men with something that will last forever, send for the Ring of Giants which is in now atop Mount Killaraus in Ireland. This Ring consists of a formation of stones that no man in this age could erect unless he employed great skill and ingenuity. The stones are enormous, and there is no one with strength enough to move them. If they can be placed in a circle here, in the exact formation which they currently hold, they will stand for all eternity…

“These stones are magical and possess certain healing powers. The giants brought them long ago from the confines of Africa and set them up in Ireland when they settled that country. They set the Ring up thus in order to be healed of their sickness by bathing amid the stones, for they would wash the stones and then bathe in the water that spilled from them; they were thus cured of their illness. They would even mix herbs in and heal their wounds in that way. There is not a stone among them which does not have some kind of medicinal power.” When the Britons heard Merlin’s words, they agreed to send for the stones and to attack the people of Ireland if they tried to withhold them. At last they chose Uther Pendragon, the brother of the king, along with fifteen thousand armed soldiers to carry out this business. Merlin was chosen so that they could be guided by his wisdom and advice. When the ships were ready, they set sail, and, with prosperous winds, made for Ireland. [Battle ensues and the Britons are victorious] Having achieved this victory, the Britons went up Mount Killaraus and gazed at the ring of stones in gladness and wonder. As they all stood there, Merlin came among them and said: “Use all of your strength, men, and you will soon discover that it is not by sinew but by knowledge that these stones shall be moved.” They then agreed to give in to Merlin’s counsel and, through the use of many clever devices, they attempted to dismantle the Ring. Some of the men set up ropes and cords, and ladders in order to accomplish their goal; but none of these things were able to budge the stones at all. Seeing all of their efforts fall flat, Merlin laughed and then rearranged all of their devices. When he had arranged everything carefully, the stones were removed more easily than can be believed. Merlin then had the stones carried away and loaded onto the ships. [The stones are transported back and celebrations are held…] the stones were set up in a circle around the graves exactly as they had been arranged on Mount Killaraus in Ireland. Merlin thus proved that his craft was indeed better than mere strength.’

~

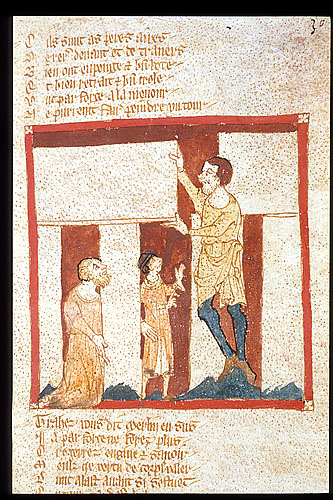

Wace’s Roman de Brut, c.1155

In the image, we see Merlin constructing Stonehenge. The inscription reads:

‘Bretun les suelent en bretanz

Apeler carole as gaianz,

Stanhenges unt nun en engleis,

Pieres pendues en francis.’

(‘In the British language the Britons usually call them the Giants’ Dance; in English they are called Stonehenge, and in French, the Hanging Stones.’)

.

~

Layamon’s ‘Brut,’ c.1215

‘The stones are great

And magic power they have

Men that are sick

Fare to that stone

And they wash that stone

And with that water bathe away their sickness’

~

Sketch in ‘Scala Mundi,’ (Ladder of the World), early 14th century

This image is quite unusual in its squared perspective.

‘Hoc anno chorea gigantum de Hybernia non vi set arte Merlini deuecta apud Stonhenges’

(That year the Giants’ Carol of Ireland, not by force but by the art of Merlin, was conveyed to Stonehenge).

The text pictured across the stones reads:

‘Stonhenges iuxta Ambesbury in Anglia sita’

(Stonehenge located near Amesbury in England).

.

~

From another copy of ‘Scala Mundi,’ c.1440

‘That year Merlin, not by force but by art, brought and erected the giants’ round from Ireland, at Stonehenge near Amesbury.’

~

John Hardyng’s ‘Chronicle,’ c.1457

‘Whiche now so hight the Stonehengles fulle sure

Bycause thay henge and somwhat bowand ere.

In wondre wyse men mervelle how thay bere’

(Which now are called the Stonehenge full sure

Because they hang and are somewhat bowing.

In wonder, wise men marvel how they keep from falling)

~

Polydore Vergil’s ‘Anglica Historia,’ c.1512

‘there deathe of there kinge, for whome, in the meane time, in that hee hadde well deserved of the common wealthe, thei erected a rioll sepulcher in the fashion of a crowne of great square stones, even in that place wheare in skirmished hee receaved his fatall stroke. The tumbe is as yet extante in the diocesse of Sarisburie, neare to the village, called Aumsburie.’

~

John Leland’s ‘Itinerary,’ c.1552

‘Kenet risithe northe northe west [of Marlborough] at Selberi Hille botom, where by hathe be camps and sepultures of men of warre, as at Aibyri a myle of, and in dyvers placis of the playne’

~

Letter by Herman Folkerzheimer to Josiah Simler, 13th August, 1562

‘At length we arrived at the place with bishop Jewel had particularly wished me to visit, and respecting which I should hesitate to write what I have seen, unless I could confirm it by most approved witnesses…

I beheld, I say, stones of immense size, almost every one of which, if you should weigh them, would be heavier than even your whole house. The stones are not heaped one upon another, nor even laid together, but are placed upright, in such a way that two of them support a third. Put forth now the powers of your understand, and guess, if you are able, by what strength, or rather by what mechanical power these stones have been brought together, set up, and raised on high?…

the bishop says, that he cannot see by what means even the united efforts of all the inhabitants could move a single stone out of its place. He is of opinion, however, that the Romans formerly erected them here as trophies, and that the very disposition of the stones bears some resemblance to a yoke.’

~

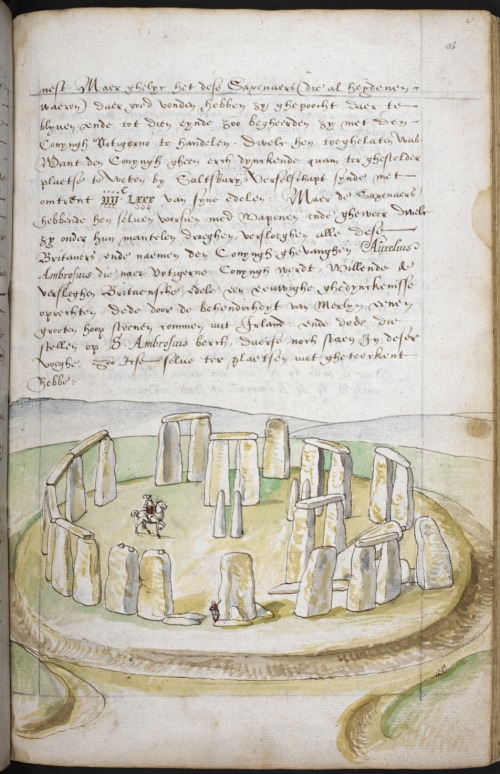

Lucas de Heere’s watercolour sketch

from ‘Corte Beschryvinghe van England, Scotland, ende Irland,’ c.1573-75

Unfortunately I was unable to find any translation or transcription of the accompanying text, which is an account of de Heere’s visit to the site.

~

William Camden’s ‘Britannia,’ c.1588

‘About six miles northward of Salisbury, on the Plains is to be seen (that I may use Cicero’s words) insana substructio, a wild structure. For within a trench are plac’d huge unhewn stones in 3 circles, one within another, after the manner of a Crown, some of which are 28 foot in height, and seven in breadth, on which others like Architraves are born up, so that it seems to be a hanging pile; from whence we call it Stonehenge, as the ancient Historians from it’s greatness call’d it Gigantum Chorea, the Giants dance. But seeing it cannot fully be described by words only, I have here subjoyn’d the Sculpture of it.

Our country-men reckon this among the wonders of the land. For it is unaccountable how such stones should come there, seeing all the circumjacent country want ordinary stones for building; and also by what means they were raised. Of these things I am not able so much to give an accurate account, as mightily to grieve that the founders of this noble monument cannot be trac’d out. Yet it is the opinion of some, that these stones are not natural or such as are dug out of the rock, but artificial, being made of fine sand cemented together by a glewy sort of matter; like those monuments which I have seen in Yorkshire. And this is not so strange: For do not we read in Pliny, that the sand of Puteol: infused in wa∣ter, is presently turn’d into stone? and that the Ci∣sterns at Rome being made of sand and strong lime, are so tempered, that they seem to be real stone? and that small pieces of marble have been so cemented, that statues made of it have been taken for one entire piece of marble?

The tradition is, that Aurelianus Ambrosius, or Usher his brother, erected it by the help of Merlin the Mathematician, to the memory of the Britains there slain by treachery in a conference with the Saxons. From whence Alexander Necham, a Poet of the middle age, in a poetical vein, but without any great fancy, made some verses, grounding them on the British History of Geoffrey (of Monmouth).

Others relate, that the Britains built this as a magnificent monument for the same Ambrosius, in the place where he was slain by his enemies; that that Pile should be as it were an Altar erected at the pub∣lick cost to the eternal memory of his valour. This is certain, that mens bones are frequently here dug up; and the village, which lies upon the Avon, is called Ambresbury’

~

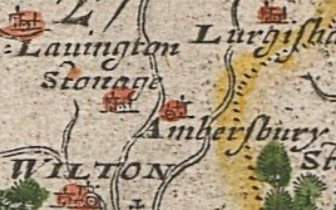

Christopher Saxton’s Atlas of the Counties of England and Wales,’ c.1590

Stonehenge is labelled ‘Stonage.’ A very small sketch can just be made out underneath.

(Header Image by English Heritage)