‘L’histoire de Guillaume de Maréschal,’ known in translation as ‘The History of William (the) Marshall,’ is a rich source of information for historians of 12th century England. It is written in verse form, with 19,214 octosyllabic lines composed in the French dialect of Touraine. It recounts the life of William Marshall, earl of Pembroke, one of the pre-eminent lords of the 12th-early 13th centuries. One event which the ‘History’ recounts, which both emphasises the unreliability of the narrative, as well as being an interesting topic of study in and of itself, is the knighting of Henry the Young King.

The Young King was the eldest surviving son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, born on the 28th February, 1155. In 1170, when young Henry was 15 years old, his father arranged for his coronation. This followed the French Capetian practice of crowning the heir apparent during the lifetime of their father, in order to ensure a smooth transition from one sovereign to the next (for those who read my last post on Lady Jane Grey, it is interesting to speculate whether such a practice might have ensured Edward VI’s plan succeeded). From that time on, the young man became known as the Young King, in order to differentiate him from his father, who was sometimes called the Old King or Elder King. Despite being formally crowned, the Young King was given little in the way of powers or authority, leading him to rebel, along with his brothers, mother, and a large faction of nobles, and with the support of the French king, Louis VII, who also happened to be his father-in-law.

Much can and has been written about the salacious details of the family relations and rebellions of ‘the Devil’s brood,’ so I won’t go into detail on this. I’m just going to focus on one of the most significant moments of the Young King’s life.

Knighting was an important moment in a young man’s life. To be a knight was to enter a binding order of chivalry, founded on military prowess and honourable conduct. Most young noblemen knew that they would one day be granted a knighthood, usually by a lord or even the king, and the son and heir of a king was no different. In ‘The History of William Marshall,’ the narrator describes a moment in 1173, during the rebellion, in which the Young King became a knight, which seems to be the epitome of chivalric tradition:

‘“But one thing, my lord. You’re not yet knighted. Not everyone’s happy with that. We’d be all the more effective a force if your sword were rightly girded: your retinue would be all the braver, prouder, in better, happier hear” The young King replied: “I will willingly do that, and I can tell you that the best knight who ever was or will be, or has done more or who is to do more, will gird on my sword, if God please.” So his sword was brought before him; and taking it into his hands he strode up to the Marshal, bold and valiant man that he was, and said: “I wish to receive this honour, good sir, from God and from you.” The Marshal had no wish to refuse; he gladly girded the sword, and kissed him, so the Young King was now a knight.’

However, there are two other accounts of the Young King’s knighting, which are in conflict with what is described by the ‘History.’ The first was a letter written by an unknown, yet clearly well connected person, to Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury. It was sent shortly after the Young King’s coronation in 1170, and recounts the archbishop with various important political events. As it is the first mentioned, it is clear that the coronation was considered of utmost importance:

‘Greetings to his lord, Thomas, archbishop of Canterbury.

(Domino suo, Thomas Cantuariensi archiepiscopo, suns Metis salutem.

Sunday having passed, the king presented his son at London with a military girdle, and immediately appointed him king by [the archbishop of] York.’

Transacta Dominica, rex apud Londonias filium suum cingulo militiae donavit, eundemque statim Eboracensis in regem inunxit…)

Whether the writer was an eyewitness to these events is unknown, though it is possible. There is another source, the ‘Chronica’ of a monk, Gervase of Canterbury, who was almost certainly present, and describes it thus:

‘Meanwhile they met on the day appointed by the king’s order to London all the bishops, abbots, and earls of England the barons, the sheriffs, the prefects, the aldermen, and their trustees, were all greatly afraid. Everyone feared according to his conscience, for they did not know what the king had decided to do. On the same day he made his son Henry, who had come from Normandy the same week, a soldier, and at once, to the astonishment and wonder of all, ordered him to be crowned king and to be crowned.’

(Convenerunt interim die statuto ex mandato regis ad Londoniam totius Angliae episcopi, abbates, comites, barones, vicecomites, praepositi, aldermanni cum fidejussoribus suis, timentes valde omnes. Quisque juxta conscientiam suam metuebat, nesciebant enim quid rex statuere decrevisset. Ipsa die Henricum filium suum, qui eadem septimana de Normannia venerat, militem fecit, statimque eum, stupentibus cunctis et mirantibus, in regem ungui praecepit et coronari.)

So we have one account which says the Young King was knighted by William Marshall three years after his coronation, and two others which say he was knighted by his father directly before his coronation in 1170. What are we to make of this?

Unfortunately, as dramatically compelling the version regaled in ‘The History of William Marshall’ is, we must discount it as untrue. And it is not just a matter of two-against-one either.

The very description of the event should raise eyebrows. It is very unlikely that young Henry would be crowned without being a knight; this was a time when military leadership was a fundamental part of kingship. Though fifteen may have been on the younger side for a knight, his brother Richard was a similar age when he was knighted by Louis VII of France. Which raises another point; one would expect the heir to the vast Angevin empire to be knighted by someone of higher status, i.e. a king. The Young King choosing the greatest and most honourable knight he knew to grant him the accolade of knighthood seems like something straight out of a troubadour’s tale.

Looking at the composition of the text also raises issues. Unlike the letter to Thomas Becket and the ‘Chronica’ of Gervase of Canterbury, the ‘The History of William Marshall’ was not contemporary; it is believed to have been started in 1224, five years after William Marshall’s death, and over 50 years after the alleged knighting took place. By that time there would have been few left to contradict the author’s version of events.

It is important to understand the context of the work. ‘The History of William Marshall’ is fundamentally a literary text. It was commissioned by William’s son, as a panegyric to his deceased father, and to entrench the illustriousness of his line. The ‘History’ casts William as the epitome of valour, honour, chivalry, and power. At best, it exaggerates many episodes of William’s life; at worst, as with the Young King’s knighting, it outright fabricates events to achieve its goal.

In summary, given the unlikelihood of the account, and the context in which i was written, it is fairly clear that the Young King was knighted before his coronation, and not several years later by William Marshall.

Unfortunately, ‘The History of William Marshall’ continues to be taken at face value and relied upon as a trustworthy source of information for both William’s life, and the political events that he witnessed and participated in. Scratching the surface of this one event in its narrative shows just how dangerous that can be.

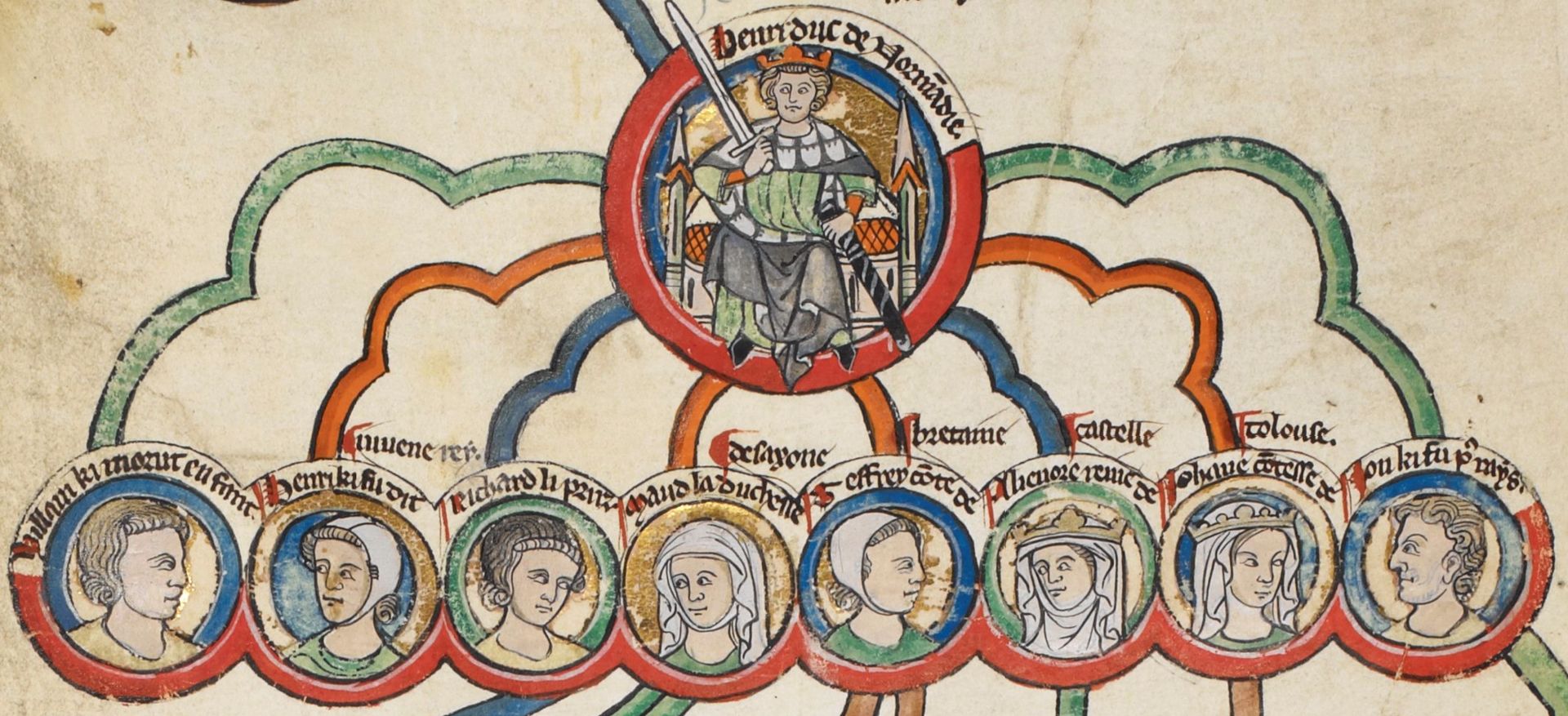

Top image: Illumination showing the Young King’s coronation, from ‘La vie de Seint Thomas de Cantorbéry,’ c.1220-1240