The so-called ‘Consort Necklace’ is one of the most famous pieces of Tudor jewellery. Appearing in a number of portraits of Henry VIII’s wives, it has actually been used to assist in the identification of at least one portrait. It was definitely worn in the portrait of Jane Seymour, the miniature of either Anne of Cleves or Catherine Howard (read here for more on this disputed portrait), and several portraits of Catherine Parr. But it has a history beyond these three women – in fact, perhaps as late as the 1590s.

The necklace is made up of “clusters” of four pearls, separated by pieces of “goldesmytheswork” set with jewels that could be switched out; usually, these were diamonds, but some depictions suggest that rubies were also sometimes used. We can see in the portraits that this necklace is usually accompanied by matching habiliments, such as the bejewelled borders of gable hoods, French hoods, and the neckline of gowns, as well as girdles. In the earlier portraits, these habiliments were of the same composition as the necklace, however, later portraits showed a greater number of pearls in the clusters, and other different but complementary adornments.

Before we dive into a discussion of the portraits, one point that I do want to make is that because of the unmoving perspective offered by portraits, it is sometimes difficult to tell how many pearls are present in a cluster; for example, in the portrait of Lady Mary, we can only see five pearls in the clusters of the habiliment across the upper curve of her French hood, however it seems probably that this is the same piece that is seen across the top of Catherine Parr’s gown in the Jersey portrait, where the different perspective allows us to see that there are in fact eight pearls in each cluster. This can further be proved, as the same habiliment, given the similar colour, perhaps even the same hood, is used across the upper curve of Lady Elizabeth’s hood in another portrait, and although we mainly see, once again, only five pearls per cluster, at the end of the habiliment, the slight change in angle reveals the third row of pearls in the final cluster.

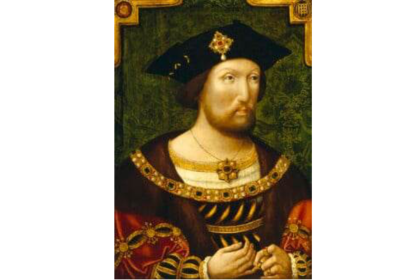

The Jane Seymour portrait is the first time we definitively see the necklace. Painted during her short reign, 1536-37, by Hans Holbein, Jane is shown wearing the Consort necklace, with the four-pearl clusters alternating diamonds set in gold. The habiliments of her gable hood, across the top of her gown, and the girdle encircling her waist are all matching in design. The part of the girdle hanging down the front is of a different design, with stylised antique amphorae pieces, and can be seen accompanying the Consort necklace on a few other occasions.

Jane received approximately half of the jewels of her predecessor, Anne Boleyn, and it has been theorised that the necklace was originally made for her. We don’t have any complete jewel inventories for Anne so we can’t say for certain, however the reconstruction of the Moost Happi Medal a few years ago brought attention to the jewellery in this unique depiction of Anne. The damage to the original medal makes it difficult to be certain, but expert analysis by the artist who created the reconstruction suggests that it seems that the necklace and hood habiliments depicted in the medal are in fact the same as those worn by Jane. This is possibly the earliest evidence of the Consort necklace and matching adornments; there has been no evidence of these pieces found in the inventories or portraits of Katherine of Aragon.

We know that Henry passed many pieces of jewellery down between his wives; these were the royal jewels, afterall, far too expensive to discard, and in fact, gave a degree of legitimacy to any new queen. We next see the Consort necklace, this time apparently set with rubies, in a Holbein miniature that is of either Anne of Cleves or Catherine Howard. In this instance, the sitter is also wearing the same pendant as Jane Seymour. However, all the other visible pieces of jewellery are different, whilst still complementary; the habiliment along the upper curve of the hood suggests an alternating pattern of single pearls, gold-set diamonds, and gold-set rubies, set apart from each other along a gold border. The remaining habiliments are also complementary, although much simpler, pearls bordering the neckline and the lower curve of the hood.

Regardless of who is depicted in the portrait, it is fairly certain that both women would have had access to the Consort necklace and accompanying accoutrements during their time as queen. Whether they both actually wore the piece, or whether it remained in the Queen’s Jewel House, it is impossible to say.

Henry VIII’s sixth and final wife, Catherine Parr, certainly wore the Consort necklace. She can be seen wearing it in the recently rediscovered and auctioned Jersey portrait. Whilst she is not wearing the necklace in the two other contemporary portraits of Catherine that have survived, she is adorned with habiliments in the same style, clearly designed to match Jane Seymour’s original set of habiliments; they may even be the same items, just remade with additional pearls.

In the Sudeley miniature by Lucas Horenbout, c.1544, Catherine’s necklace, and the habiliments bordering the neckline and lower curve of her French hood are made up of simple rows of pearls. The upper curve of her hood, however, is made up of five pearls with the same diamonds set in gold. I think it is likely that this is one of the habiliments found in the earlier portraits, just with an additional pearl added to the top of each cluster, in order to increase the magnificence of the piece; Catherine was known for her love of rich clothing and jewels, so this is not surprising.

The full length portrait of Catherine, by an artist known as Master John, shows her again wearing one of the matching habiliments without the necklace, this time with the traditional four-pearl clusters, along the lower curve of the French hood.

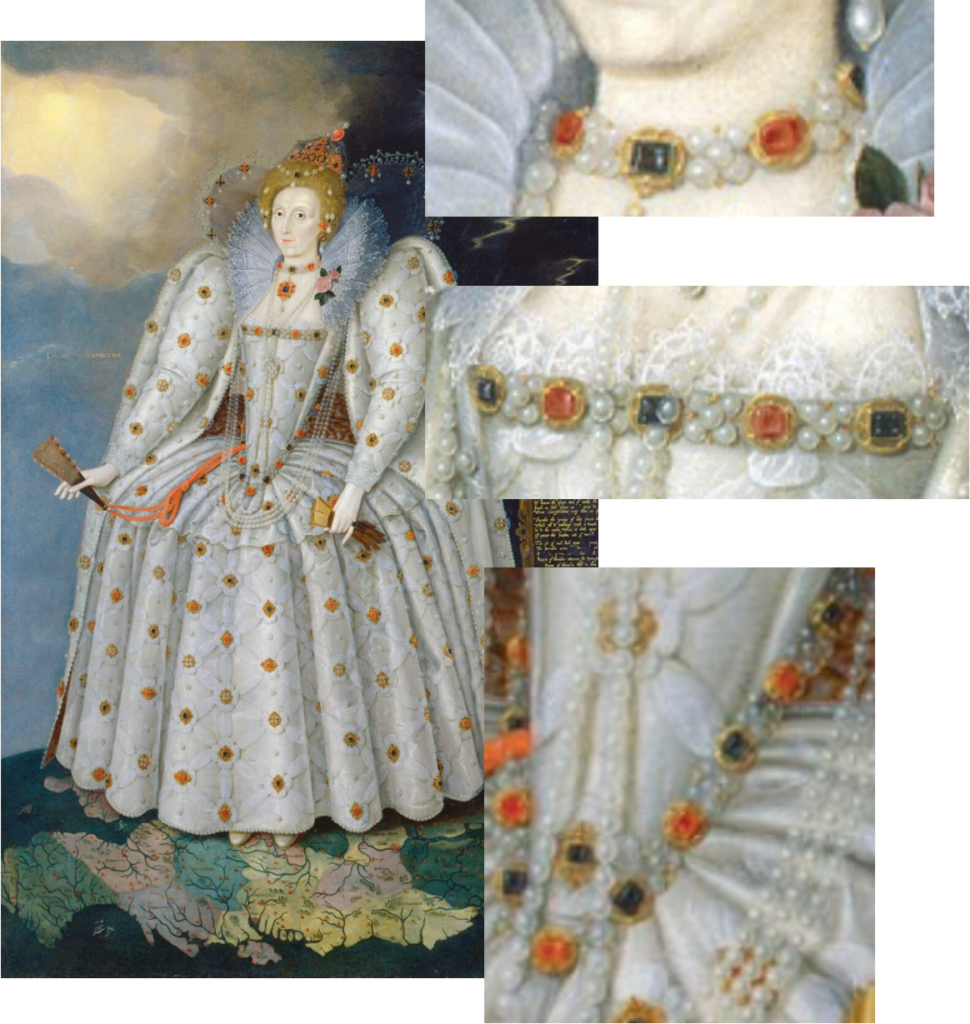

And of course we finally have the Jersey portrait of Catherine that I mentioned before, also by Master John. This is the only portrait of Catherine wearing the Consort necklace itself, along with new variations of the habiliments. This portrait shows Catherine at her most queenly and magnificent by far. The habiliment along the neckline has at least eight pearls in every cluster, whilst the girdle has at least five, in both cases the clusters are separated by the same diamonds set in gold found in the consort necklace. The amphorae chain hanging from the girdle is the same as that worn by Jane Seymour. Unlike the previous examples of French hoods, both the upper and lower curves are bejewelled, the lower having an alternating pattern of two pearls and a gold piece. The upper curve is similar to the Anne of Cleves/Catherine Howard, this time with alternating clusters of three pearls and diamonds set apart from each other along a gold border. Whilst the richness of some of these pieces has increased since Jane Seymour’s day, they clearly follow the same style, intended to still match the Consort necklace.

Catherine Parr was known for lending her jewellery to her favourite ladies. Although the Consort necklace itself was not worn by anyone else, the matching habiliments were used in portraits of Catherine’s stepdaughters, Lady Mary and Lady Elizabeth.

A portrait of Mary was painted in 1544 by Master John, and one of Elizabeth by William Scorts in in 1546, however the jewels they wear are remarkably similar. Both are depicted as wearing the same habiliment on the upper curve of their French hoods as Catherine Parr wears on the neckline of her gown in the Jersey portrait, although the limited angle only allows five of the eight pearls in each cluster to be seen, with the exception of the end of Elizabeth’s hood, where the full number can be seen. Both of their necklaces are alternating single pearls and gold beads, as are the habiliments on the lower curve of their hoods. However, whilst Mary’s neckline has a habiliment of the same single pearls and gold beads, Elizabeth’s neckline and girdle habiliments are the same as that of the upper curve of her French hood, and thus also the same as Catherine’s neckline in the Jersey portrait, making for a much more ornate ensemble. The chain hanging from her girdle, with its amphorae, is also the same as in the Jersey portrait and Jane Seymour’s. Catherine had a very close relationship with both of her stepdaughters, so there was probably no particular reason for lending more ornate jewellery to one than the other; if anything, as the elder, Mary would expect to be given the higher status pieces. Perhaps this is a clue as to when these habiliments were restyled to have more pearls; they were simply not available when Mary’s portrait was made.

Upon Henry VIII’s death, the royal jewels (as opposed to Catherine’s personal jewels) were seized by the Lord Protector and moved to the Tower of London, much to the outrage of Catherine and her new husband, Thomas Seymour. The Consort necklace would have been amongst these, although whether the accompanying habiliments were also seized is unknown. As Edward VI had no Queen Consort, the Consort necklace remained unworn. These royal jewels would next have been taken out when Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed Queen, not as a consort, but as Regnant in her own right. Whether she wore this necklace as a symbol of legitimacy and continuity with previous queens, we can only guess. She would not have had long to enjoy these jewels before she was arrested 13 days later (you can read more about the length of Jane’s reign here) and Mary was proclaimed Queen.

We have several portraits proving that Mary did wear the Consort necklace and matching habiliments. In the most famous portrait of Mary as Queen by Antonis Mors, painted in 1554, she is wearing the necklace (although the artist seems to have missed one of the diamonds) along with what appears to be the same habiliment Catherine Parr wears in the Sudeley miniature, with five-pearl clusters. Mary wore this combination in one other portrait, the one depicting her with her husband, Philip of Spain. Additionally, she also wears a girdle with alternating two pearls and one gold-set diamond in the same style. Mary wore the hood habiliment in several other portraits, though without any of the other matching pieces.

Upon Mary’s death, her sister, Elizabeth, inherited the throne, and thus, the royal jewel collection. Whilst Elizabeth does not seem to have worn the Consort necklace, one element of this set of jewellery can be found dotted throughout Elizabeth’s portraiture. This is the habiliment comprising five-pearl clusters and gold-set diamonds, worn by Catherine Parr as a girdle in the Jersey portrait and as the hood habiliment in Mary’s portraits as Queen.

One of the earliest portraits of Elizabeth after she became queen was painted in 1560, and shows her wearing this piece, although now with gold accents within the pearl clusters. A few years later, Van Meulen painted Elizabeth with these five-pearl cluster habiliments, this time as part of the French hood; it is difficult to make out amongst other layers of ornamentation, but I’ve tried to make it as clear as possible in the image. In the Darnley portrait, c.1575, Elizabeth once again wears this piece as a girdle, as well as the pearl and gold bead necklace she had worn as a girl.

Almost two decades later, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger painted the famous Ditchley portrait of Elizabeth. In it, Elizabeth appears to wear a necklace, neckline and girdle very similar to the five-pearl cluster and jewel pieces last portrayed decades earlier, although the gold pieces at this time were set with alternating rubies and diamonds. It is hard to tell whether these are actually the same pieces. Perhaps as she entered the twilight of her reign, Elizabeth became nostalgic for a reminder of her youth, and had the piece retrieved from the Jewel House, or perhaps recreated from memory.

We don’t know the precise fate of the Consort necklace and matching habiliments; Anne of Denmark, Queen Consort of James VI/I does not appear to wear any of these pieces in her portraiture. If they were still part of the royal collection at the time of the Civil War, they would have been either destroyed or sold off by Oliver Cromwell and his supporters, as were all of the Crown Jewels.