Some things never change, and graffiti is one of them. Examples of graffiti can be found going back thousands of years. During the Middle Ages, everyone was expected to attend Sunday Mass. However, unless you were an educated cleric or nobleman, most of the Latin service would have been unintelligible. Whilst standing around (any pews were reserved for the wealthy) waiting for the service to finish, people would quietly talk and do business – and commit a little bit of petty graffiti. Medieval church graffiti offers a unique insight into the lives of ordinary people.

Some are as simple as a cartoon or the culprit’s name, whilst others are far more clever and complex. Occasionally, this graffiti took the wonderfully clever form of a rebus, a puzzle device which takes the form of letters and pictures to spell out a word or phrase.

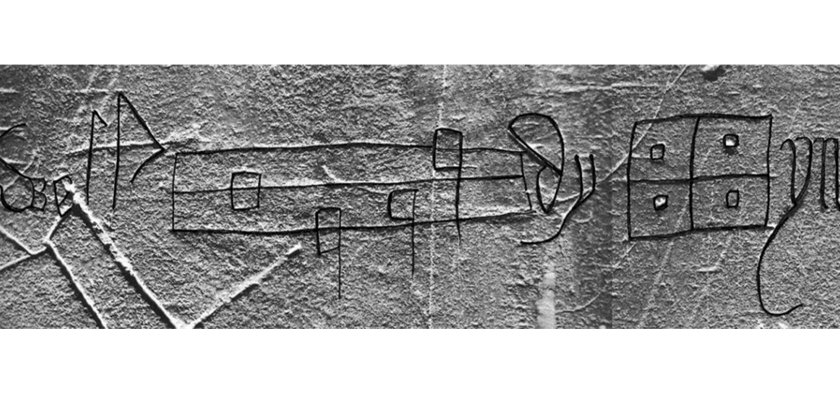

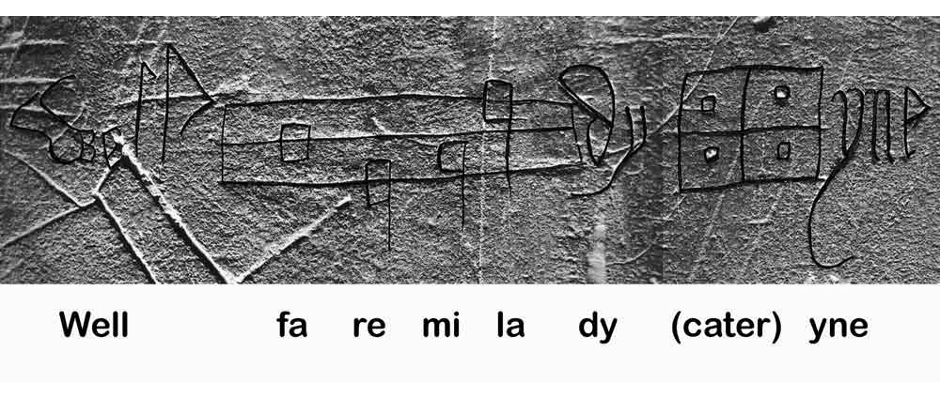

My favourite example of a medieval rebus is a delightful 15th century graffito carved into a wall of St. Mary’s Church in Lidgate, Suffolk. You can see an image of the rebus below. We start with the word ‘WELL,’ which is followed by a short piece of musical notation, with the notes C, A, B, E. Next, are the letters ‘dy,’ a square with four dots, and ending with the letters ‘yne.’

So, what are we to make of this?

As early as the 11th century, musicians ascribed the famous syllables most people know from ‘The Sound of Music’ – do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti – to musical notes. The notes from the rebus – C, A, B, & E – were fa, re, mi, & la. If you put these syllables together with the letters directly before and after, you get the phrase ‘Well fare, mi lady.’

What about the square? This is actually a pictogram of a dice with four pips, which was known in the Middle Ages as a ‘cater.’ Add the final letters of the rebus, this makes the name ‘Cateryne,’ a form of the name Catherine.

So, all together, the rebus becomes:

‘WELL FARE, MI LADY CATERYNE’

Who left this lovely carving, and who is Lady Cateryne?

Well, we do have an answer for at least the first question, as it appears the same hand that carved the rebus was also responsible for at least one other carving in the church:

‘Johannes Lydgate fecit hoc licencia in die sancti Symonis et iude’

Which translates to ‘John Lydgate made this by licence on the day of Saint Simon and Jude. The feast day of Saints Simon and Jude was the 28th October.

So it is fairly certain that the author of the rebus was John Lydgate, who was also the author of the Valentine poem I wrote about in February, which you can read here.

John Lydgate grew up in Lidgate, which is probably what his surname derived from. In his youth, before first monastic life and then literary fame took him away from his home town, he was a self-confessed trouble maker: ‘lied to excuse myself. I stole apples … I made mouths at people like a wanton ape. I gambled at cherry stones. I was late to rise and dirty at meals. I was chief shammer of illness.’ So it isn’t really surprising that he would defile a church with graffiti.

Lydgate certainly had the mind and the skill to create such a puzzle. He went on to be one of the most prolific and prominent poets of his age. He was patronised by many nobles, and even kings. In fact, it has been suggested that one of his royal patrons may be the key to the identity of Lady Cateryne.

Henry V first patronised Lydgate in 1412, a year before he became king. In 1420, Henry married a French princess, Katherine of Valois. It has been suggested that this is the ‘Lady Cateryne’ referred to in the rebus. At least one other of Lydgate’s poems is about Queen Katherine, The Temple of Glas.’

Personally, I am not convinced by this identification. Whilst it is possible that he would refer to Queen Katherine as ‘mi lady’ in order to fit his clever puzzle, it seems rather informal. In addition, the small village church of St. Mary’s was hardly somewhere anyone of note would see the tribute. If the poem was to Queen Katherine, it would have to have been written after Lydgate’s literary career was well-established, and we have no evidence of Lydgate spending time in his town during this period of his life.

I tend to think that it is just as likely that he came up with the rebus as an amusing demonstration of his talent for language, with no particular woman in mind. Regardless, it is a delightful puzzle, which continues to titillate minds centuries later.