The relationship between Henry II and Thomas Becket is legendary; from closest of friends to the worst of enemies. Given that it ended in the brutal murder of Thomas in his own cathedral, it is hard to imagine just how close they had been.

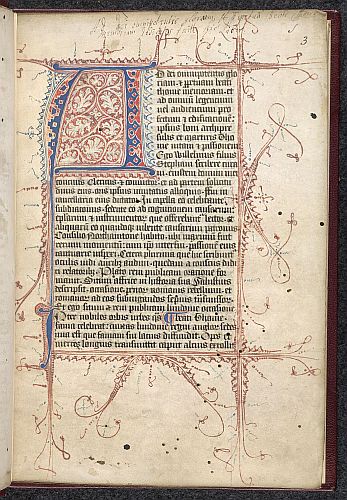

There is one episode that William Fitzstephen recounts in ‘Vita Sancti Thomæ,’ his biography of Thomas, to illustrate their intimacy during the years when Thomas served as chancellor:

TRANSLATION:

‘Thus, on account of his virtue, magnanimous soul, and great merits, the chancellor was most endeared to the King, the clergy, the soldiers, and the people. When their work was done, the King and himself played together, like boys of the same age, at court, in church, in assemblies, and when riding. One winter’s day, they rode together in the streets of London; from a distance the King saw an poor old man coming along, his clothes worn and thin; and he said to the chancellor, ‘See! How poor, how weak, how poorly clothed this man is! Would it not be a great alms to give him a thick, warm cloak?’ Chancellor Becket: ‘Immense indeed, and for such a mind and eye, my King, you ought to have.’ Meanwhile, they came upon the poor man; the King stopped, and the chancellor with him. The King calmly addressed the poor man, and asked if he would like to have a good cloak. The poor man, not knowing who they were, thought it a joke, not to be taken seriously. The King turned to the chancellor: ‘Well, you will give this great alms’; and laid his hands on the chancellor’s new and best cloak of scarlet and grey, which he had put on. The King laboured to take it from the chancellor, and he to retain it. There was a sudden cause of conflict between them; neither would tell their onlooking retinue what was happening; each was intent on his hands, so that at one time they seemed about to fall. The chancellor, after a while, reluctantly, endured to admit defeat, and took off his cloak bowing to himself, and to give it to the poor man. The King then told the story to his retinue, who held out their cloaks and mantles to the chancellor. When the chancellor’s cloak came to him, the poor old man went away, enriched beyond hope and happy, giving thanks to God.’

ORIGINAL LATIN:

‘Ita ob ipsius dotes virtutum, animi magnitudinem, meritorum insignia, quae animo ejus inhaeserant, cancellarius regi, clero, militiae et populo erat acceptissimus. Pertractatis seriis, colludebant rex et ipse, tanquam coaetanci pueruli, in aula, in ecclesia, in consessu, in equitando. Una dierum coequitabeant in strata Londoniae; stridebat deformis hyems; eminus aspexit rex venientem senem, pauperem, veste trita et tenui; et ait cancellario, “Video!’ Rex, ‘Quam pauper, quam debilis, quam nudus! Numquidne magna esset eleemosyna dare ei crassam et calidam capam?’ Cancellarius, ‘Ingens equidem; et ad hujusmodi animum et oculum, rex, habere deberes.’ Interea paupaer adest; rex substitit, et cancellarius cum eo. Rex placide compellat pauperem, et quaerit si capam bonam vellet habere. Pauper, nesciens illos esse, putabat jocum, non seria agi. Rex cancellario, ‘Equidem tu hanc ingentem habebis eleemosynam;’ et injectis ad capucium ejus manibus, capam quam novam et optimam de scarleta et grysio indutus erat, rex cancellario auferre, ille retinere, laborabat. Fit igitur ibi motus et tumultus magnus: divites et milites, qui eos sequebantur, mirati accelerant scire quaenam esset tam subita inter eos causa concertandi; non fuit qui diceret; intentus erat uterque manibus suis, ut aliquando quasi casuri viderentur. Aliquandiu releuctatus cancellarius, sustinuit regem vincere, capam sibi inclinato detrahere, et pauperi donare. Tunc primum rex sociis suis acta narrat; risus omnium ingens; fuerunt qui cancellario capas et pallia sua porrigerent. Cum capa cancellarii pauper senex abit, praeter spem locupletatus et laetus, Deo gratias agens.’

Traditionally, this tale has been interpreted as two friends having a playful squabble; Thomas was known for enjoying the finer things in life, including his clothing, whilst Henry was noted for his complete lack of fashion – hence one of his nicknames, Curtmantle, as he often wore an unfashionably short mantle. The episode demonstrates their intimacy as how many would dare to resist and tussle with the King in such a way?

However, recently there has been a move to reinterpret it. Some historians are reading a darker undertone into the behaviour, saying that Henry was demonstrating his absolute power and authority that even his chancellor and closest friend had to submit to.

This theory does not hold with me, personally; Henry was king, of course he had absolute power and authority, there were no questions about that. Furthermore, Becket’s later actions clearly show that he had no problem resisting the will of his King. It is important for historians to not retrospectively and anachronistically interpret events based on what would come later.

However, in this case, considering later events does raise other questions about this episode. William Fitzstephen, the author of this account, served in Becket’s household for many years, first as a clerk and then a subdeacon, and was given considerable power and authority to act on Becket’s behalf. However, when Becket was forced into exile, Fitzstephen was pardoned by the King and given several important positions within the English judicial system; clearly he had earned the trust and respect of both men. He was well placed to witness and see the interactions between Henry and Becket during their many years of friendship and then their many years of feuding.

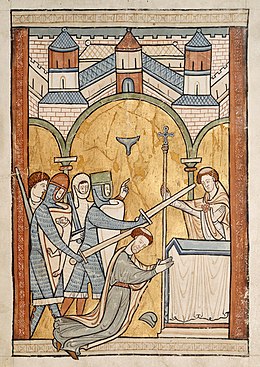

However, Fitzstephen was writing this biography of Becket in the 1170s, after Becket’s brutal death; not only that, when Becket had returned to England, Fitzstephen had returned to his household, and personally witnessed the archbishop’s martyrdom.

Almost immediately after Becket’s death, a cult grew up around him, with people claiming his blood could perform miracles. It was a powerful image; the Archbishop of Canterbury being cut down in his own church due to his defence of the Mother Church against the king. Fitzstephen’s biography reflects this.

Chroniclers and writers had a very different approach to history and truth than modern historians do; they were more concerned with conveying ideas and themes rather than authentically relating events that had verifiably happened. Fitzstephen’s biography was meant to show the holiness of Becket. The first few pages of the ‘Vita’ discuss omens and prophetic visions of Becket’s greatness that were made in his infancy and childhood, events that were never mentioned before his death. Right from the first page, right from his infancy, Fitzstephen was foreshadowing Becket’s martyrdom.

So what does that mean for this particular event? Perhaps it did happen just as Fitzstephen describes. However, it is possible that it was invented both as an illustration of the relationship between the two men, and as another piece of foreshadowing; the king and Becket fighting over a matter of religion, almsgiving; Becket being forced to submit, and having his worldly possessions ripped from him; but in return, receiving God’s favour for his good works.

This would be in keeping with much of Fitzstephen’s work. Unfortunately, this is one event that we will never know for sure about. It is a wonderful tale, regardless.

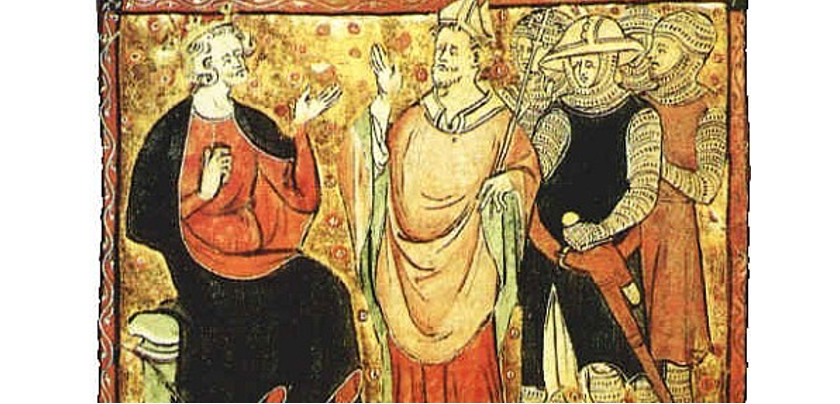

Top image: 14th century illustration of Henry II and Thomas Becket from Liber Legum Antiquorum Regum