On the 12th May, 1546, a young Prince Edward wrote a letter to his stepmother, Catherine Parr, that sheds an interesting light on Edward’s early religious education.

‘Prince Edward to Queen Catharine,

Pardon my rude style in writing to you, most illustrious queen and beloved mother, and receive my hearty thanks for your loving kindness to me and my sister.

Yet, dearest mother, the only true consolation is from Heaven, and the only real love is the love of God. Preserve therefore, I pray you, my dear sister Mary, from all the wiles and enchantments of the evil one ; and beseech her to attend no longer to foreign dances and merriments which do not become a most Christian princess. And so, putting my trust in God for you to take this exhortation in good part, I commend you to his most gracious keeping.

From Hunsdon, this 12th of May.

Edward the Prince.’

How should we interpret Edward’s exhortations against dancing?

It is commonly believed that it was only after Edward became king that his relationship with his sister, Mary, deteriorated over matters of religion. Whilst their father was still alive, there was a strong bond between the pair; indeed, just four days before this letter, Edward wrote to Mary that ‘I love you most.’ But could this letter to Catherine be the earliest sign of a strain in Edward and Mary’s relationship? Was this an indication that they were on different paths?

Actually, whilst religion was clearly the subtext of Edward’s concerns over Mary’s ‘foreign dances and merriments,’ I don’t think we can say that they indicated much about his personal religious position at this time. We must remember, Edward was not yet nine years old at the time of writing. Although Edward received the best education available, he was still a few years away from the religious extremism that would later so drastically affect his relationship with his sister.

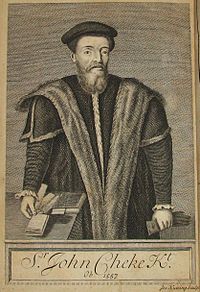

However, I think ‘education’ is the key here. Edward was being taught by John Cheke and Richard Cox, two leading proponents of the Reformation. Though neither of them were Puritans, they both leaned far more strongly towards Protestantism than the Henrician Church of England, particularly Cheke. Whilst we do not have any definitive evidence on their views on dancing, it seems likely that Cheke and/or Cox followed the Protestant rejection of ‘dances and merriments,’ as they distracted from studying the Gospel and worshipping God.

I think that in his letter to Catherine, the eight year old Edward was echoing something one of his tutors had said. Perhaps they had specifically named Mary, or perhaps Edward had heard a more generalised comment on proper Christian conduct and had made the mental leap himself to apply it to his sister. It certainly wasn’t a sentiment that he had learned from Catherine; she shared her stepdaughter’s love of music and dancing.

If it was something he had heard within a day or two, it makes sense why Edward mentioned it in his letter to his stepmother, but failed to make any sought on direct appeal to Mary; it was something that had caught his attention, but that he didn’t fully understand, and once a few days had passed, it was gone from his mind again. Anyone who has been around young children will recognise this type of parroting of ideas they hear without fully understanding.

The letter is more a reflection of the influences surrounding the young prince, the men who were shaping and molding his mind, rather than a direct reflection of what Edward personally believed at this time. From this letter, we can see the influences that would cause Edward to become a Protestant extremist. But in 1546, Edward was too young to understand the nuances of religious morality.

This is all completely speculative, of course. But it is interesting to try and unravel the thought processes behind the sources.

Top image: Portrait of Prince Edward by William Scrots, c.1546