On the 21st April, 1509, Henry VII died. His death was kept a secret for two days whilst arrangements were quietly made; his health had been declining for months, and he had been receiving fewer and fewer visitors, which made it easier for his counsellors to keep up appearances, entering and exiting the late King’s apartments as though nothing were amiss. Not even his son, the new King Henry VIII, was aware that his father had passed and that he was now king.

Thomas Wriothesley, the Garter King of Arms, made a record of Henry VII’s final days and death. His entire account makes for fascinating reading. The most compelling feature, though, is a small sketch that he made of the deathbed. In the centre lies the dying King, surrounded by the members of his inner circle. As Garter King of Arms, Wriothesley was intimately familiar with the coat of arms of all the noblemen in the room, and he very helpfully provided illustrations of the arms of the most significant men in the room: Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester; George, Lord Hastings; Richard Weston, Esquire of the Body and Groom of the Privy Chamber; Richard Clement, Groom of the Privy Chamber; Matthew Baker, Esquire of the Body; John Sharpe, Gentlemen Usher; William Tyler, Gentlemen Usher; Hugh Denys, Esquire of the Body; and William Fitzwilliam, Gentleman Usher. Dotted in between these lords and gentlemen are two tonsured clerics and three physicians holding what is believed to be urine bottles. We don’t know the identities of the physicians, but they may have been William Altofte, Thomas Linacre, and John Chambre, all of who served at Henry VII’s court as royal physicians.

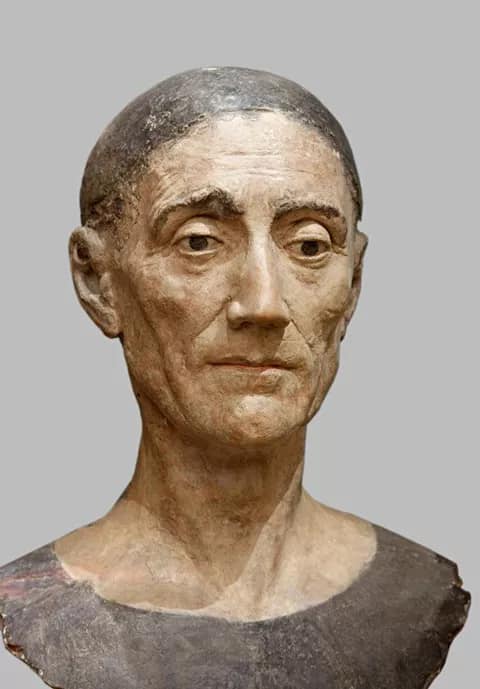

The face was probably cast from a mould taken from the death mask or cadaver of Henry VII

It is interesting to consider the poses of the figures. The Bishop of Winchester has his hands folded, clearly leading the prayer, whilst the others, with the exception of the physicians who have their hands full, have their hands raised, palms turned outward, in the orans prayer posture, receiving and expressing their prayers for their king. In addition to the physicians, there is one other exception; William Fitzwilliam can be seen closing his dead master’s eyes.

It is unclear whether Thomas Wriothesley was personally present to witness this sad, yet significant, moment in time, or whether he invented the scene based on what he was later told. Unfortunately, this also means we do not know whether this group of men were all present as Henry passed away. Regardless of whether he was there or not, the illustration is clearly meant to be representative and not literal; it is unlikely the dying king was actually wearing his crown as he died. These were the men who knew of the king’s death when it occurred and kept the secret until a plan was in place to ensure the smooth ascension of the new king.

Although the phrase would not be used in England for a few more centuries, the sentiment still applied: The King is dead; long live the King!