Historians and genealogists owe a huge debt of gratitude to Thomas Cromwell. It is thanks to him that we have an extremely valuable source of information about the lives of ordinary people down the generations, their births, their marriages, and their deaths. I’m talking, of course, about the parish registry.

On the 5th September, 1538, Cromwell, in his role as Vicar General, presented before Henry VIII a series of Injunctions, instructions to the clergy on they must operate in the still-new Church of England. Seventeen new rules were laid down on a variety of church matters, from the keeping of an English Bible in every church, to the licensing of preachers.

The document begins:

‘Exhibit quinto die mensis Septebr ano dni Mie Vc XXXVIII.

In the Name of God Amen. By the authorite and comission of the excellent prince Henry by the grace of god kynge of Englond and of frauce, defensor of the faithe Lorde of Irelonde and in erthe supme hedd vndre Christ of the Church of Englonde, I Thomas lorde Crumwell, lorde privie seale Vice-gerent to the kynges said highnes for all his Jurisdiction eccliasticall within this realme, do for the avancement of the trewe honor of almighty God, encrease of vertu and discharge of the kynges maiestie geve and exhibite vnto yow theise Iniuctions folowing to be kept obsued and fulfilled vpon the paynes hereafter declared’

(In the name of God, Amen. By the authority and commission of the excellent prince Henry, by the grace of God King of England and of France, defender of the faith, lord of Ireland, and in earth Supreme Head under Christ of the Church of England, I, Thomas lord Crumwel, lord privy seal, Viceregent to the King’s said highness for all his jurisdictions ecclesiastical within his realm, do for the true honour of Almighty God, increase of virtue, and discharge of the King’s majesty, give and exhibit unto you—these injunctions following, to be kept, observed, and fulfilled, upon the pains hereafter declared)

The twelfth item on the list concerned the keeping of a parish register to record all christenings, weddings, and burials, the manner they should be recorded in, how the documents should be kept, and the fines for failing to maintain accurate records:

‘Item that yow and eny pson vicare or curate this dioc shall for euery churche kepe one boke or reistre wherin ye shall write the day and yere of every weddyng christenyng and buryeng made wtin yor pishe for yowr tyme, and so euy man succedyng yow lykewise. And shall there inserte euy psons name that shalbe so weddid christened or buried, And for the sauff keping of the same boke the pishe shalbe boude to puide of there comen charges one sure coffer with twoo lockes and keys wherof the one to remain wt you, and thother with the saide wardons, wherein the saide boke shalbe laide vpp. Whiche boke ye shall every sonday take furthe and in the psence of the said wardens or one of them write and recorde in the same all the weddinges christenynges and buryenges made the hole weke before. And that done to lay vpp the boke in the said coffer as afore And for euy tyme that the same shalbe omytted the partie that shalbe in the faulte therof shall forfett to the said churche IIIs IIIId to be emploied on the repation of the same churche.’

(Item, That you, and every parson, vicar, or curate within this diocese, shall for every church keep one book or register, wherein ye shall write the day and year of every wedding, christening, and burying, made within your parish for your time and so every man succeeding you likewise ; and also there insert every person’s name that shall be so wedded, christened, or buried; and for the safe keeping of the same book, the parish shall be bound to provide, of their common charges, one sure coffer with two locks and keys whereof the one to remain with you, and the other with the wardens of every such parish wherein the book shall be laid up ; which book ye shall every Sunday take forth, and in the presence of the said wardens, or one of them, write and record in the same all the weddings, christenings, and buryings, made the whole week before; and that done to lay up the book in the said coffer as before; and for every time that the same shall be omitted, the party that shall be in the fault thereof shall forfeit to the said church 3s-4d, to be employed on the reparation of the same church.)

We don’t know where Cromwell got the idea for the parish registry. Such records were unknown in England in the Middle Ages. In the early 16th century there is evidence of one or two parishes implementing such schemes, but they seem to have been conceived by their local priests, and were not widely nor well-kept.

It has been suggested that Cromwell encountered parish registers in his youth in Italy; several Italian cities had been keeping parish records since the late 14th century. However, this is speculation, and there is no proof that Cromwell would have been situated to notice parish administrations.

But why did Cromwell bring in such a scheme? Again, we can’t know for sure, but different historians have put forward a number of theories.

One school of thought is that it was implemented to settle inheritance; having a record of who was related to whom, and how, was of enormous use when someone disputed a will based on closer blood relation than another.

Another idea that has been suggested is that it was to help settle marital disputes: being able to trace the consanguinity of a couple who wished to marry, or separate based on consanguinity, made matters much simpler.

However, Cromwell was notoriously slippery; could he have had more sinister intentions? People at the time certainly thought so. One of the rumours which spurred on the Pilgrimage of Grace in the north of England was that christenings, weddings, and burials would be taxed. To the south, Piers Edgecombe reported that in Devon and Cornwall, people feared that churches would be forced to:

‘make a book wherein is to be specified the names of as many as be wedding and buried and christened. Their mistrust is, that some charges more than hath been in times past shall grow to them by this occasion of registering.’

Luckily for the people of England, for the moment, this turned out to be mere rumour and nothing more.

Diarmaid MacCulloch put forward a very interesting idea in his biography of Cromwell. He suggested that it was part of Cromwell’s plan to uncover and wipe out any Anabaptists in England. This reform sect began in the Low Countries in the 1520s, but was persecuted by Roman Catholics and Protestants alike. All of the Tudor monarchs regarded them as dangerously radical, due to the violent uprisings associated with their activities in the Low Countries. One of the core beliefs of the Anabaptists was that baptism was only valid when the person could make a confession of faith, which infants were obviously unable to do, and therefore the Anabaptists opposed infant baptism, performing only adult baptism. By implementing a register of christenings, it would be easy for parish authorities to see who had failed to have their baby baptised, and to act accordingly. Henry VIII instituted a number of laws regarding Anabaptism, and there were persecutions. Was the introduction of the parish register an attempt to further persecute this sect?

Knowing Cromwell, I wouldn’t be surprised if there was an element of truth in each of these theories; though a tax was not implemented at that time, that may well have been his long-term plan.

All subsequent Tudor monarchs contributed to the development of the parish register.

In 1547, Edward VI reissued Cromwell’s order, providing an amendment that the penalty should ‘be employed to the poore box of that parishe’

In 1555, under Mary I, Cardinal Pole added that sponsors should be included in the baptismal records:

‘Whether they do keep the Book or Register of Christeming, Burying, and Marriages, with the name of the Godfather and Godmother.’

Under Elizabeth I, the parish register was considered to be of such importance that new ministers had to swear to maintain it:

‘Every minister, at his institution, should subscribe to this prostestation, “I shall keepe the register booke according to the Queene’s Majesties injunction.”’

In 1597, the keeping of the records was further regulated. Whilst previously the parish records had been kept haphazardly on any random pieces of parchment, from thenceforth all records had to be entered into a dedicated book, with entries backdated to the start of Elizabeth I’s reign. Though the precise wording of the new rules has been lost, we know of it from references in the said parish books, for example:

‘Register booke for the parish church of Beeston-next-Mileham, to recorde all such their names as shall be within that parish either christened, maryed, or buried accordinge to the booke of constitutions and canons of the parliament in the yeere 1597. The number of sheets herein 13 with 18 leaves of every sheet, in all 244. The price of the parchment io/- and for the bindynge 2/-.’

As a historian, all I can say is, whatever his motivations, thank goodness Cromwell decided to implement this invaluable record system.

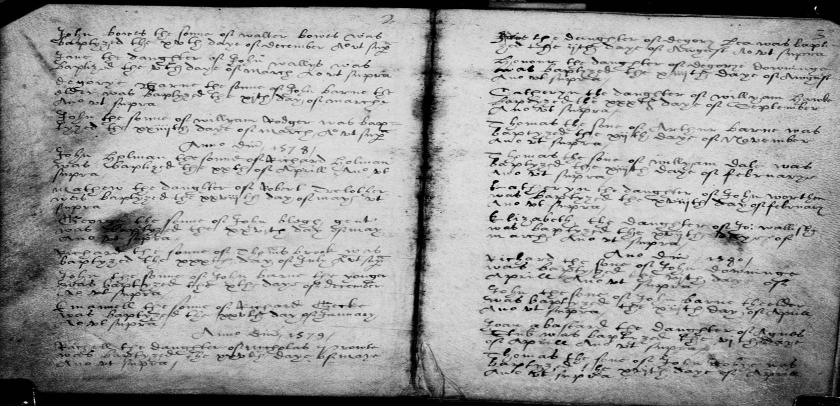

Top image: 1577-1580 Christenings, Egloskerry Parish Registers, Cornwall